Introduction by Quincy Jones

Afterward by Steven Albahari

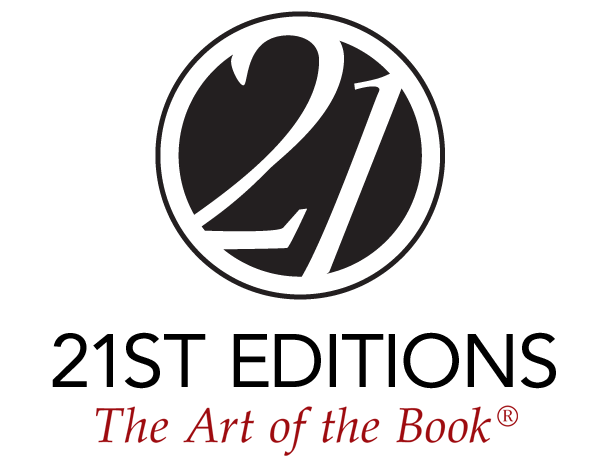

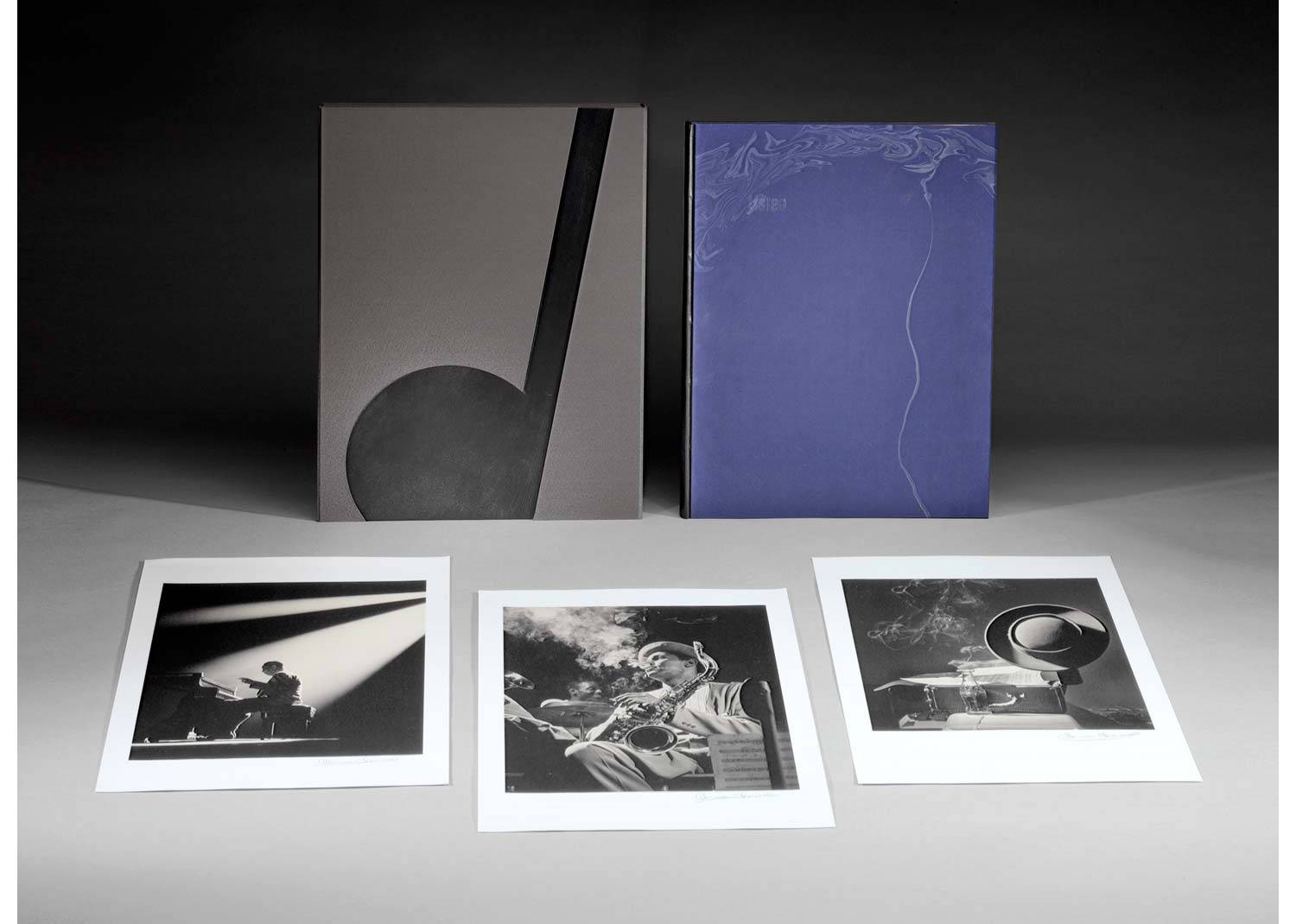

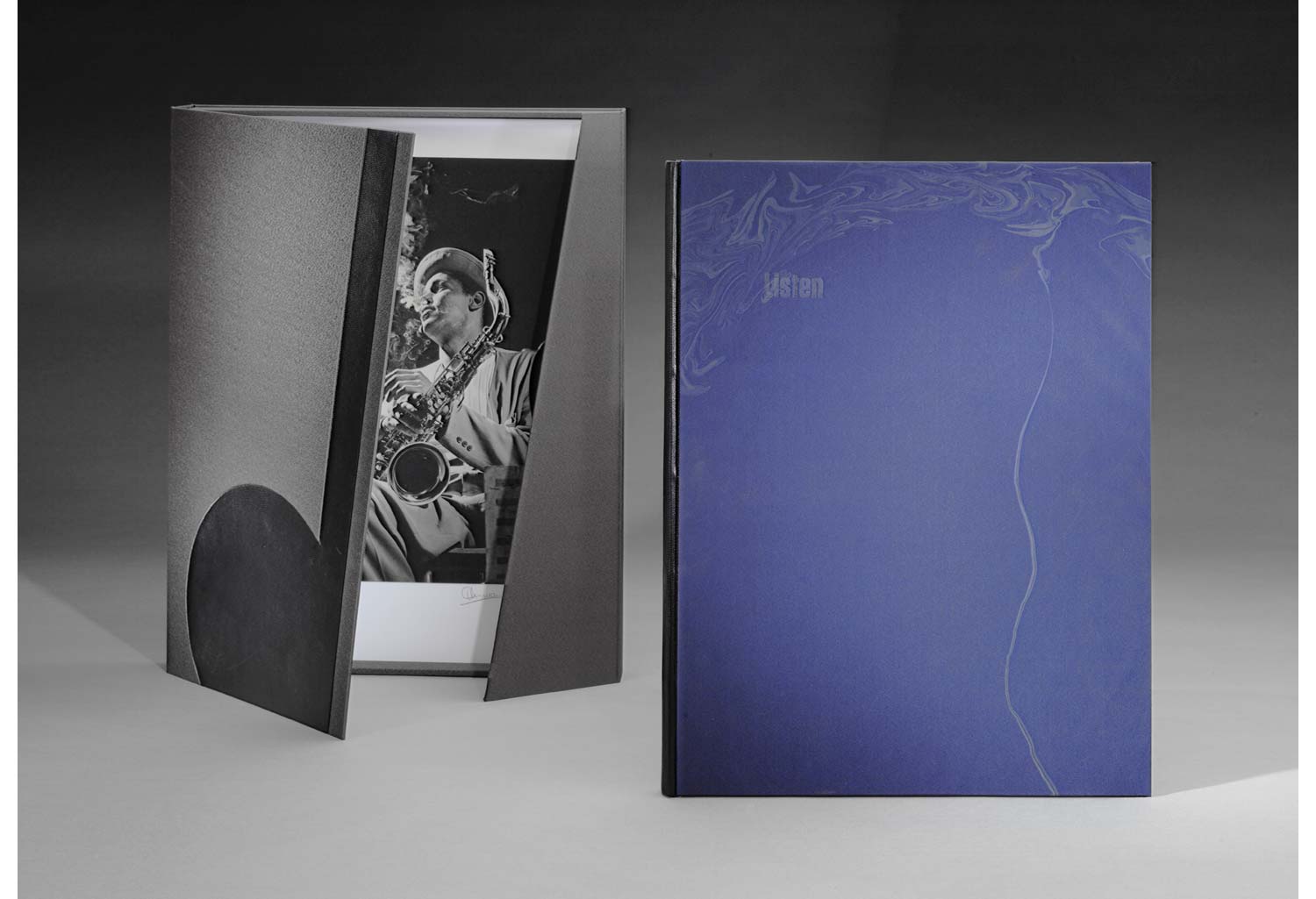

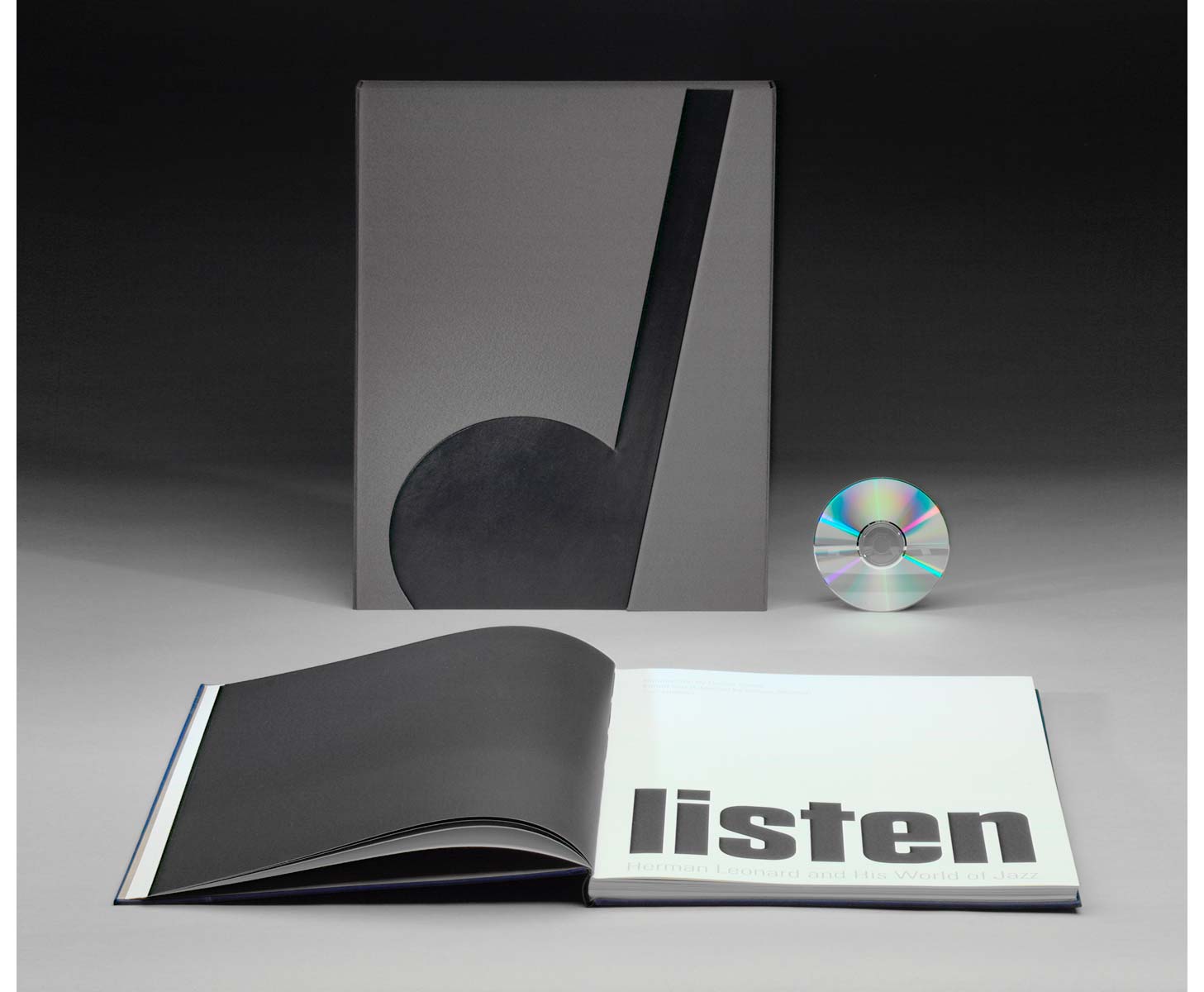

Edition: 40 numbered and 10 lettered copies

Includes 9 bound and 3 loose platinum prints (each signed on the mount),

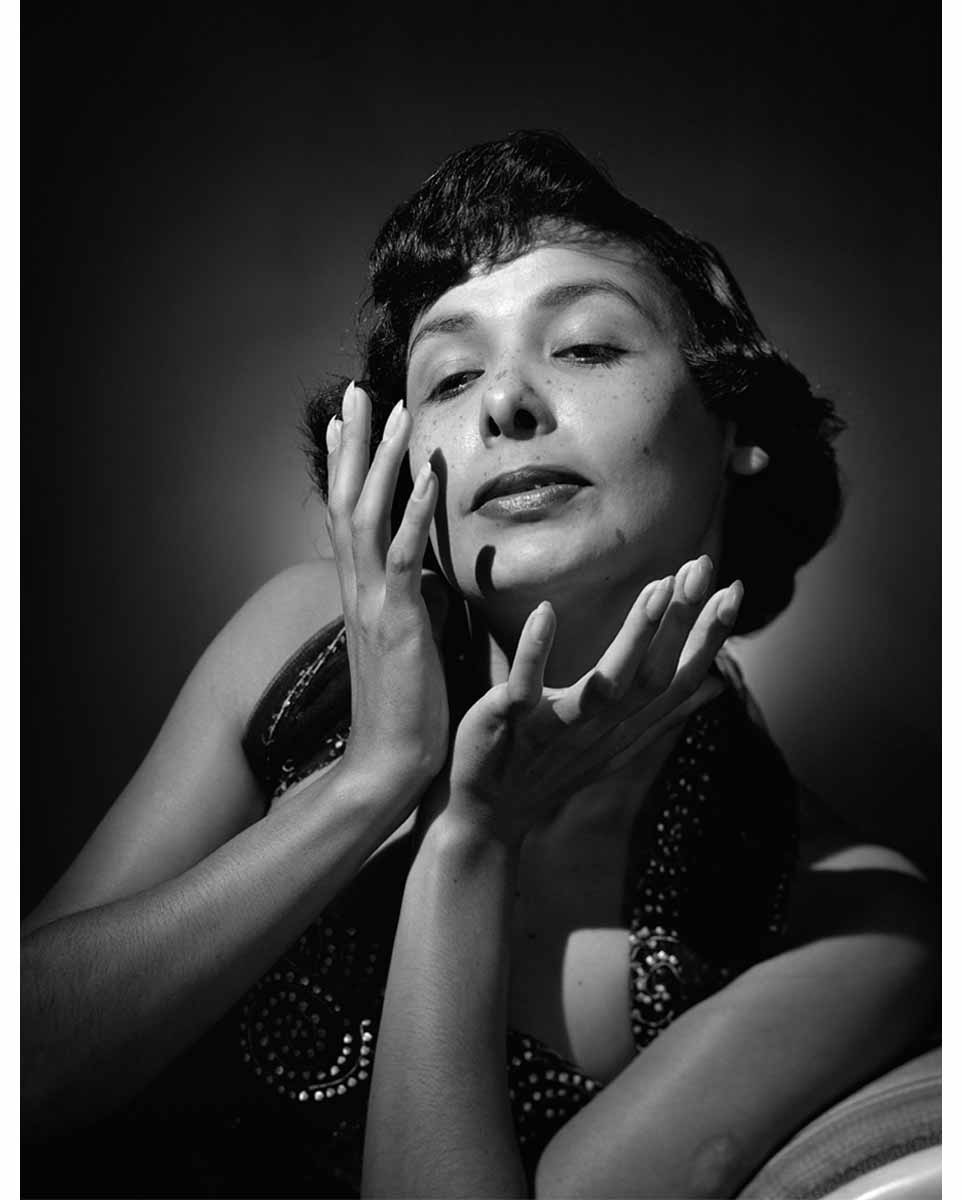

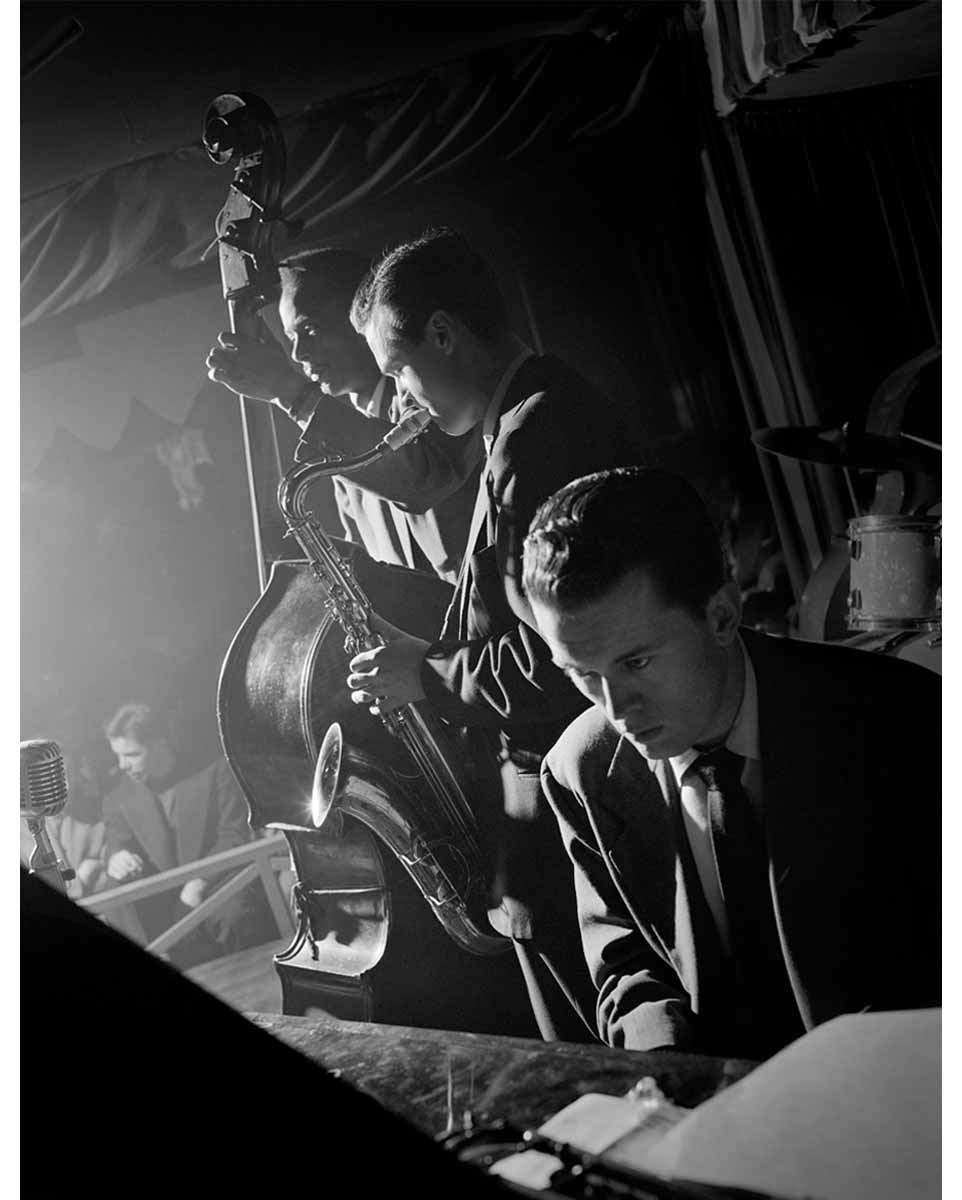

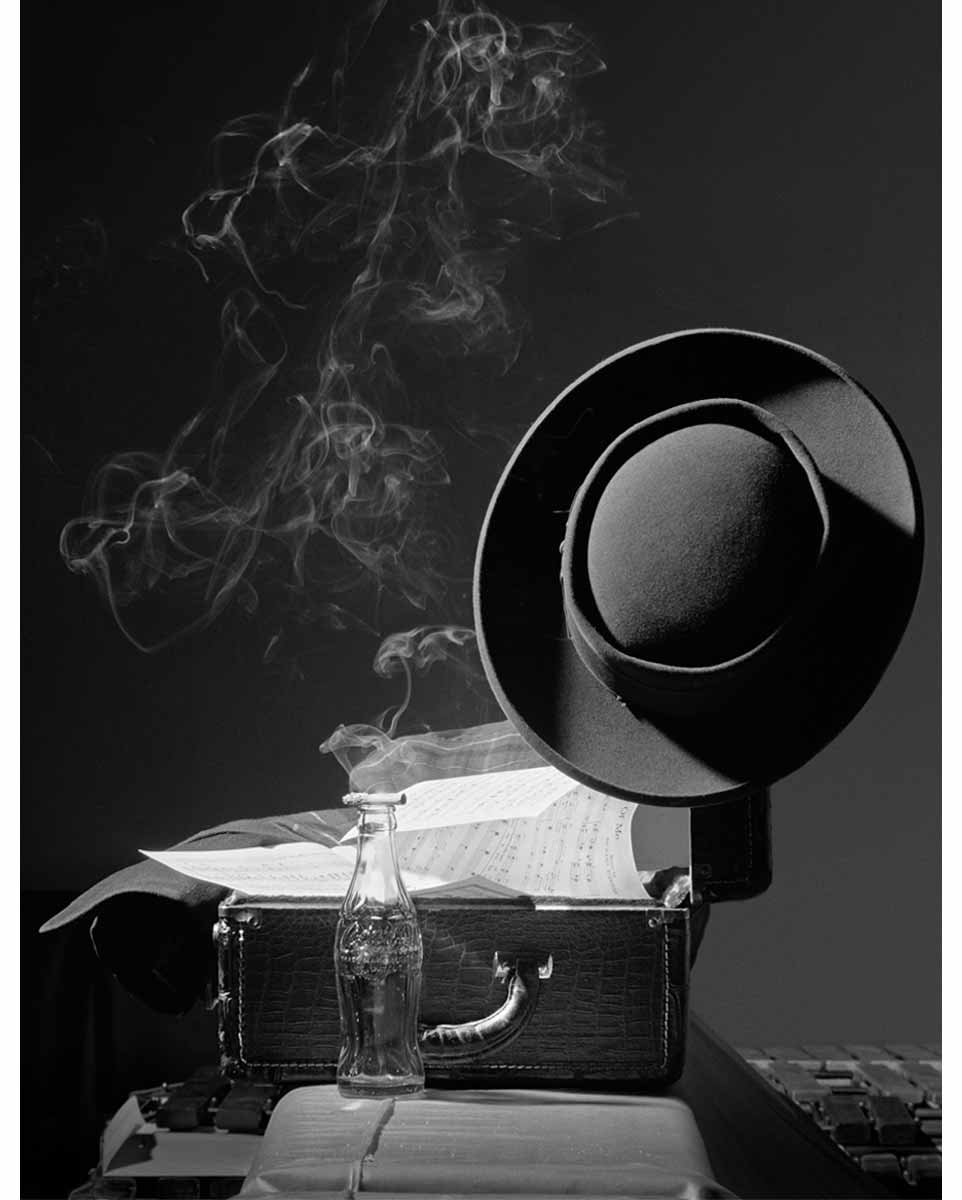

Dexter Gordon, Duke Ellington, and Lester Young’s Hat.

17 1/2 x 13 1/2 inches

Handcrafted in New England

Click here to watch Herman Leonard seeing Listen for the first time.

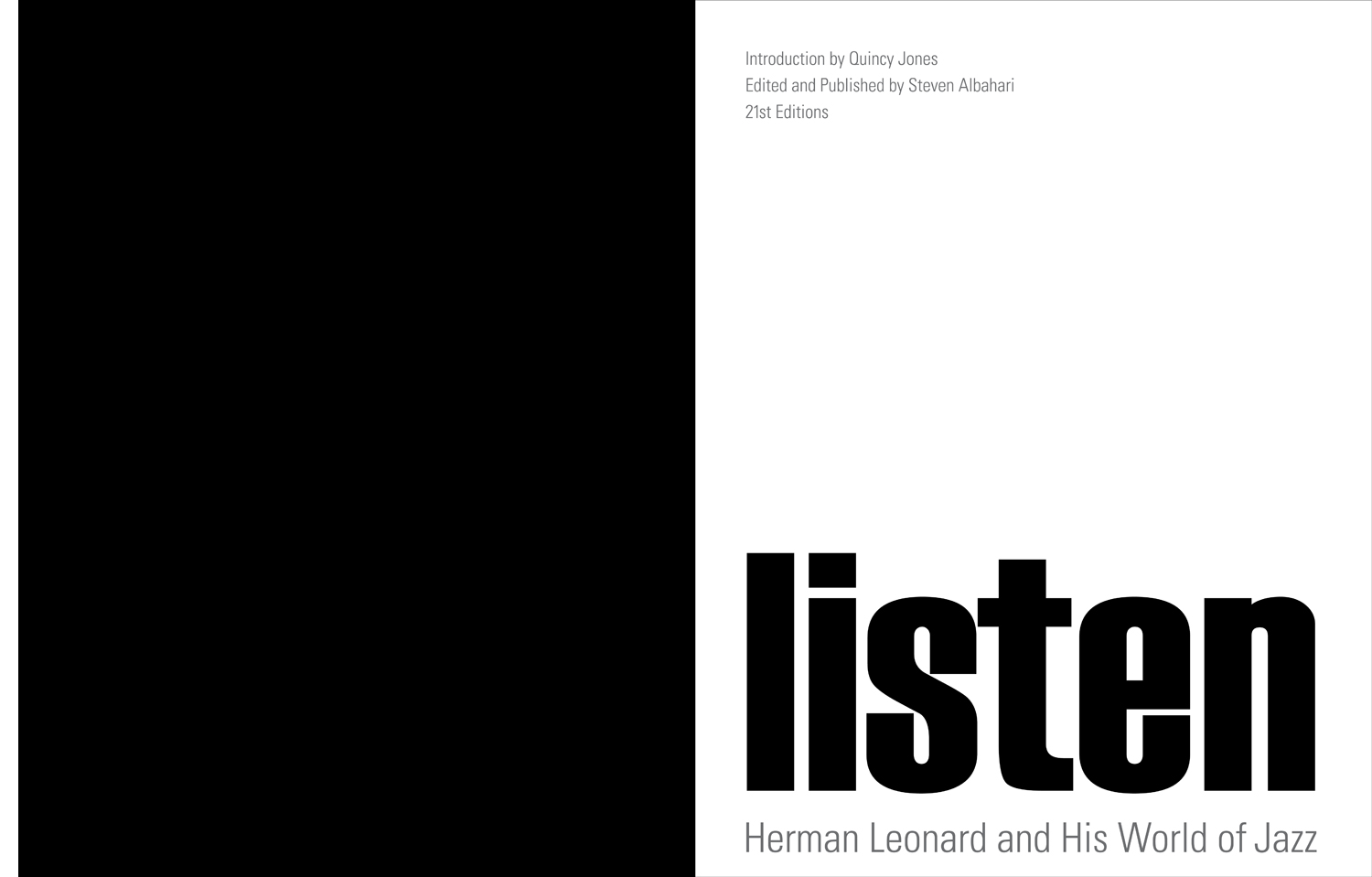

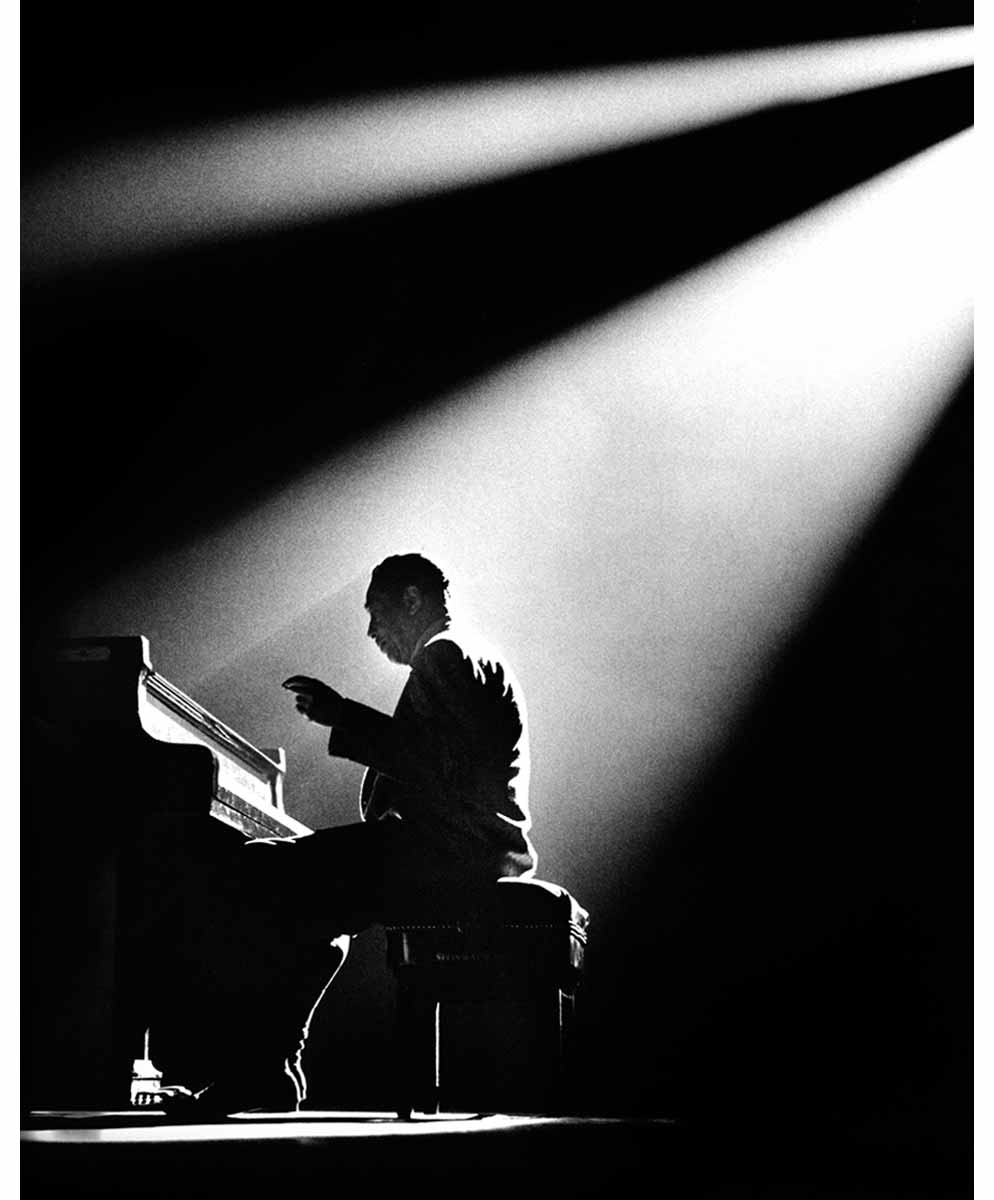

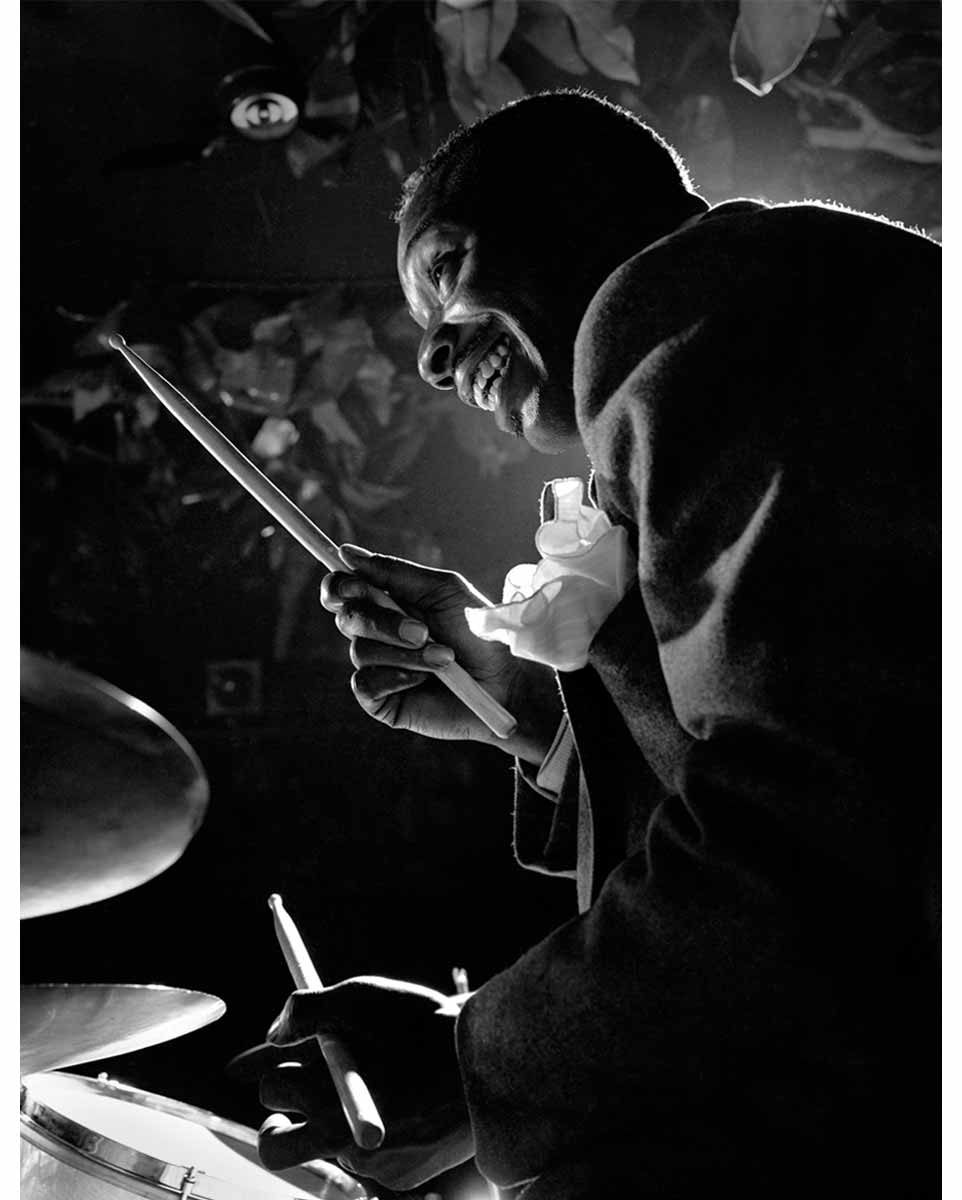

Today people talk a lot about “reading” a photograph. That means “getting it,” understanding what it’s all about. But, man, when it comes to Herman Leonard, I think a better verb is listen. You need to “listen” to Herman’s pictures. They are full of music and you can hear it. Just look at his great picture of Lady Day. If you can’t hear her singing to that little angel over her left shoulder, then you’re just not listening. Herman’s pictures always swing—and always have some special touch, like that angel, that leaves you wondering where it came from. Look at The Duke seated at his piano. It’s Ellington,

for sure, but notice how Herman caught him in those modernistic and elegant shafts of black and white light, which echo Ellington’s elegant, always new music.

I’ve often called Herman’s photographs “perfect.” But his perfection was no accident, no piece of good luck. He did have the good luck, or the smarts, to be in a lot of the right places at the right time. But he learned his craft, the notes and scales of his art, just like we musicians did. Before you can go off on a riff, you’ve got to know where the notes are, and Herman learned all his camera’s notes. He realized at a young age the value of studying with a master and apprenticed with Yousuf Karsh, who wrote that Herman had what it took “to be a great photographer.”

Herman and I have known each other since the early Fifties when I was playing with Dizzy Gillespie’s band. Then in Paris in the late Fifties, and right on till today. And he’s always caught that swing, which is why we musicians always wanted Herman to photograph us. He made us look like our music sounded because he had come to his art the same way we came to ours—by finding our own distinct voices. If there’s ever been a musician’s photographer, it’s been Herman Leonard. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, his photographs are music to my eyes. And most of all, I have been blessed to have him as my brother and friend for so many years.

The introduction by Quincy Jones