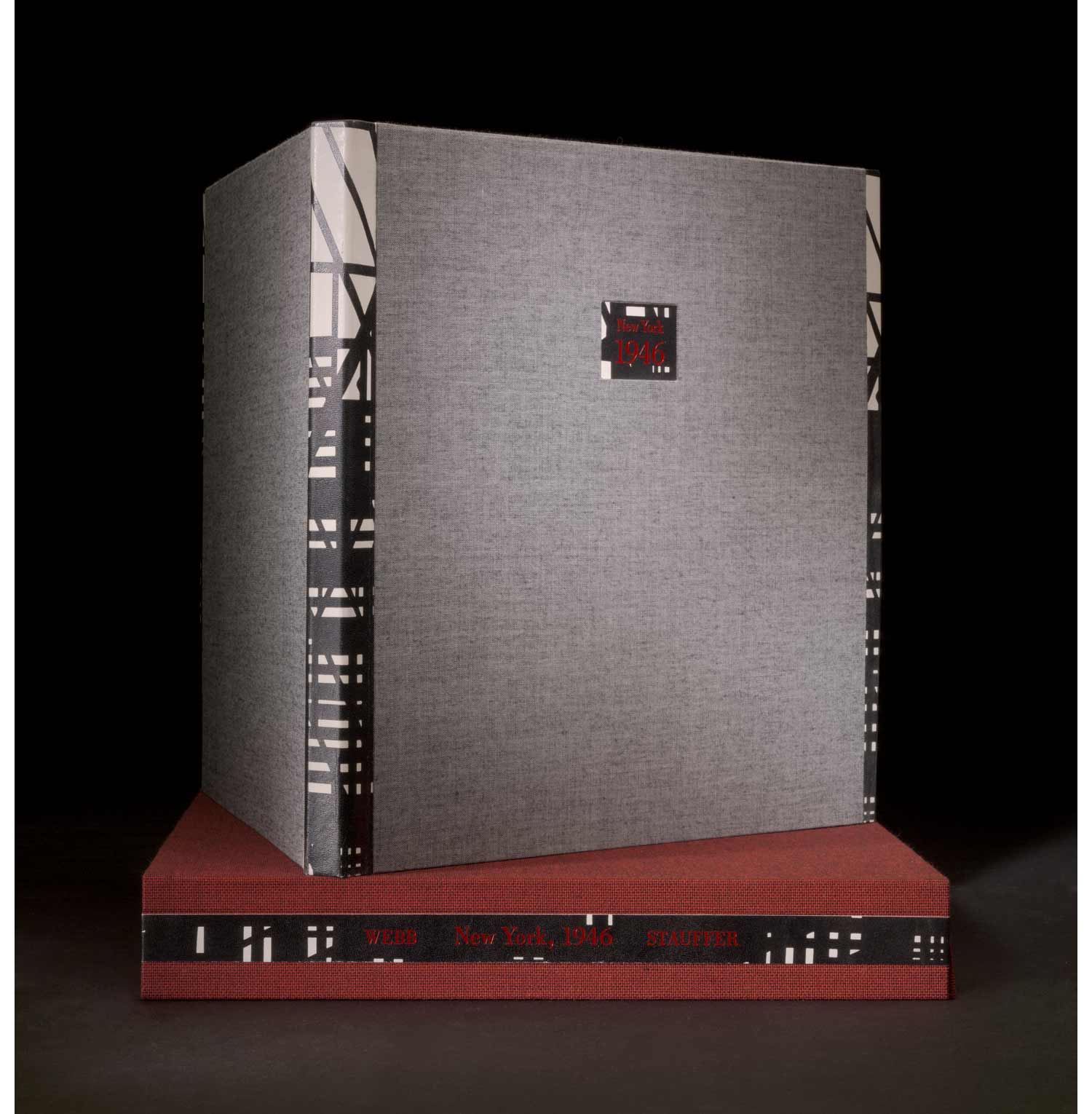

The beginning of this year brought a new Editor to 21st Editions, John Stauffer. John's credentials are numerous (a tenured Harvard Professor with 15 books, more than 100 articles, scholarly awards, and much more). He continues to offer a rich historical context for the photographs and artists represented in many 21st Editions titles.

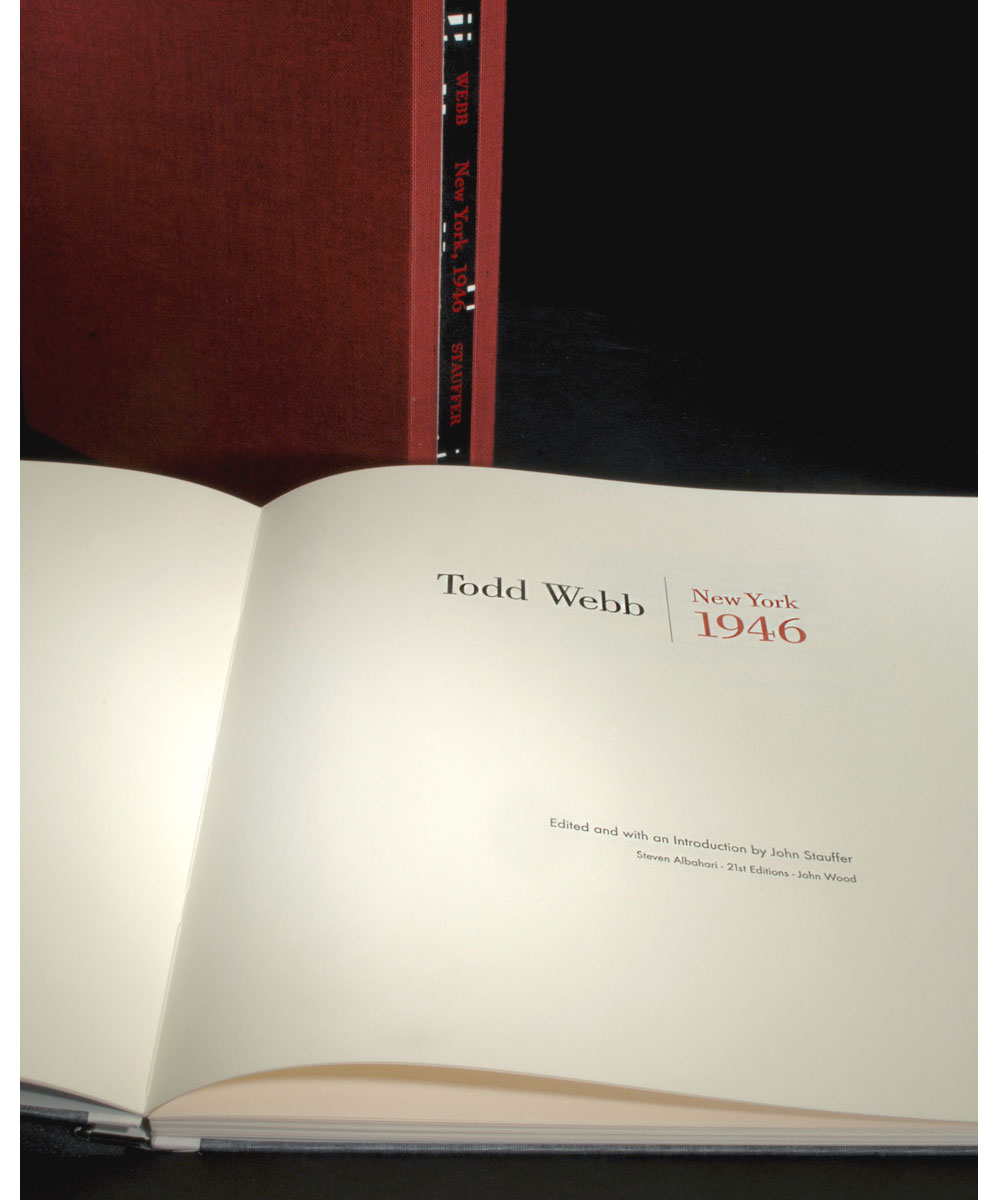

JOHN STAUFFER ON

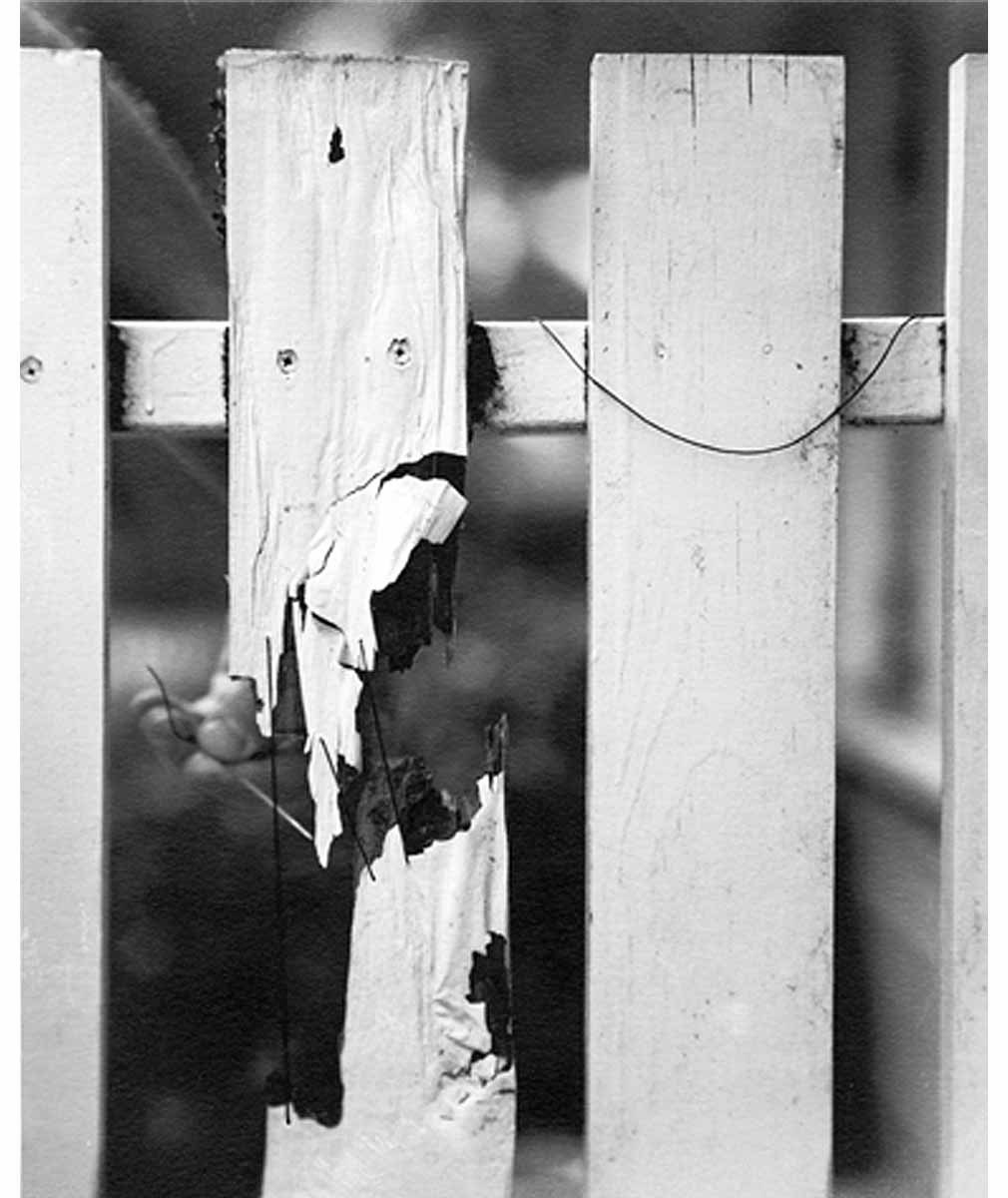

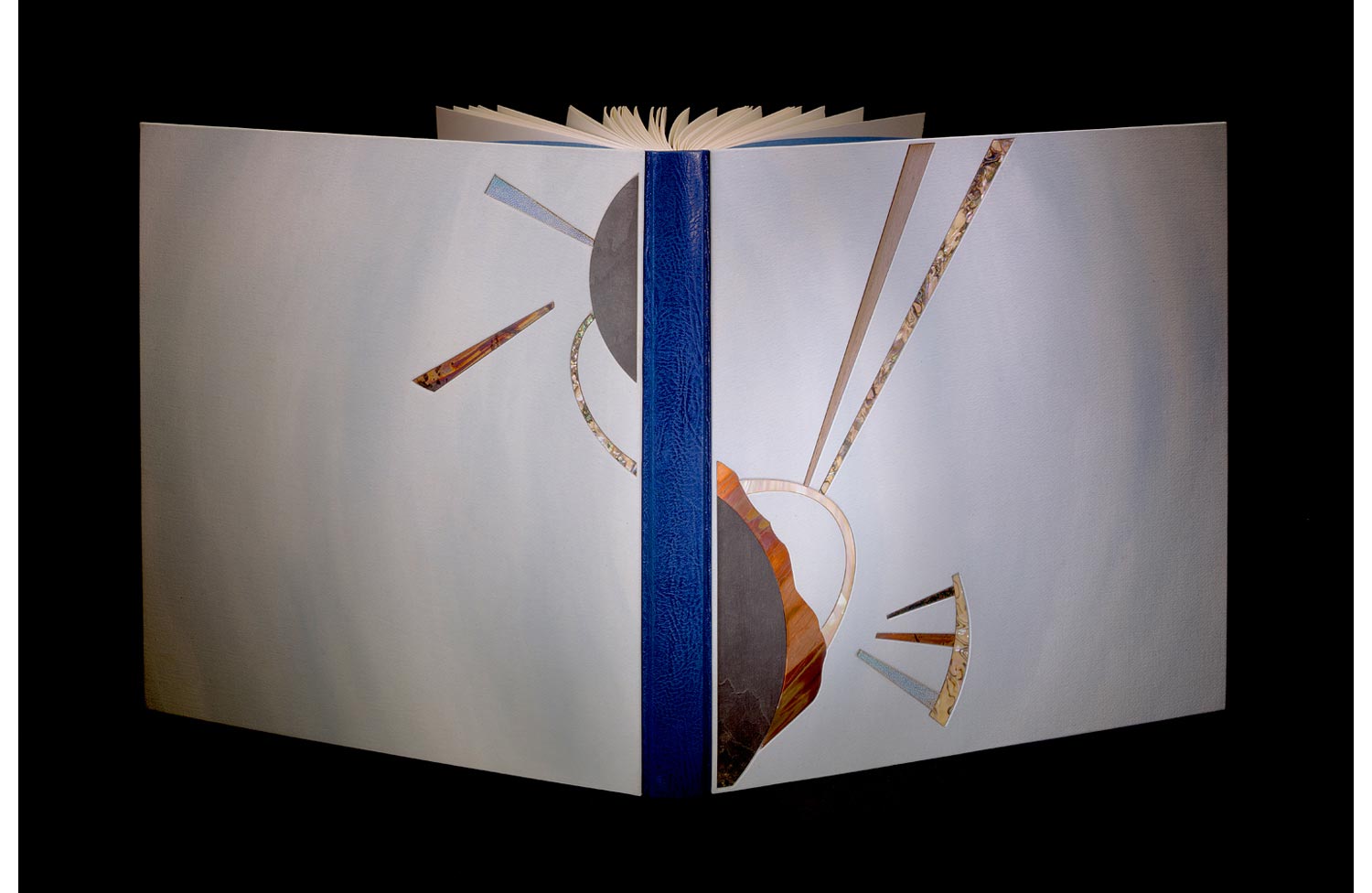

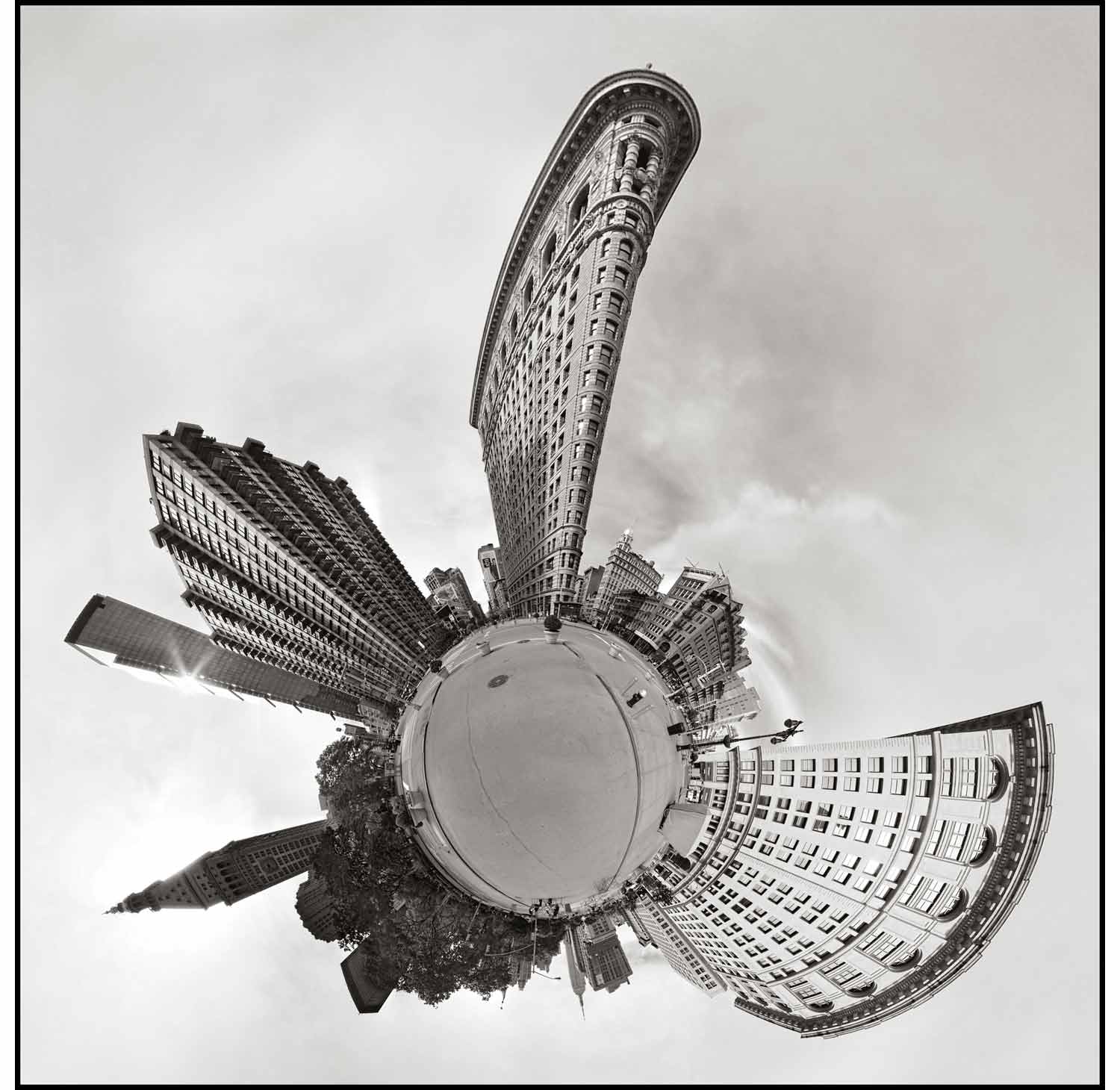

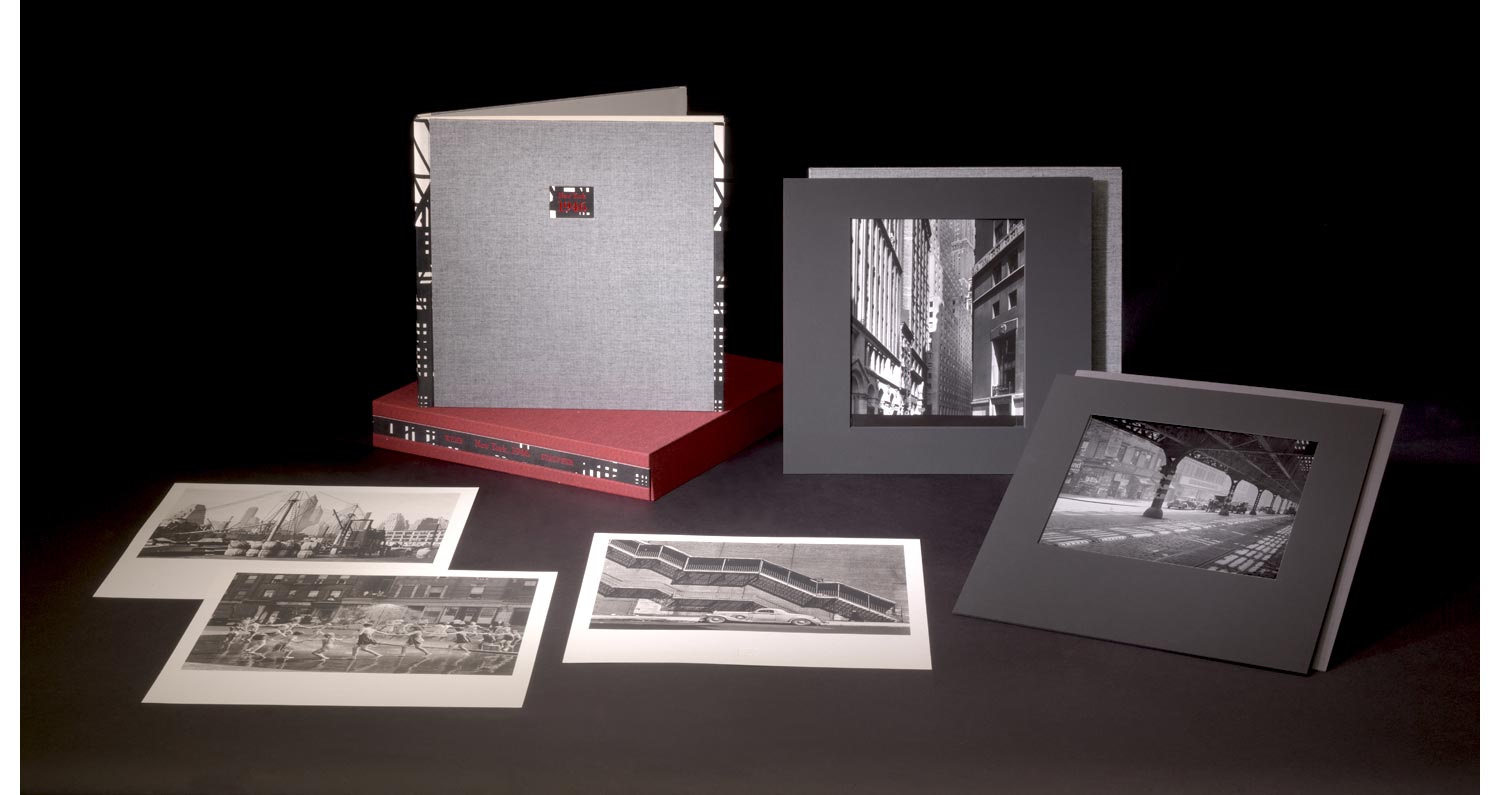

Todd Webb: New York, 1946

When Todd Webb arrived in New York in November 1945, Henry Luce's famous prophecy, uttered five years earlier, that the U.S. would become the "leader of the world" and launch an "American century," seemed to have been realized. The war had made America rich and powerful while decimating much of Europe, and artists flocked to its cultural center. There was now talk that New York might replace Paris as the world center of art and culture, as Serge Guilbaut has noted. But "it was important to find the right image for America and its culture," which would "mirror the experience of [the] age." This image would need to resonate with the formal and ideological sensibilities of New York and the U.S., as well as the rest of the art world. In painting, abstract expressionism would become that image. Jackson Pollock's seemingly random drips of paint evoked an existential angst that mirrored the "experience of the age."

In photography, the idea and image of the city became the symbol of the new postwar world. In 1946 alone, Webb shared the streets of New York with Helen Levitt (with whom he sometimes photographed), Berenice Abbott, André Kertész, Minor White, Gordon Parks, Aaron Siskind, Paul Strand, Andreas Feininger, Weegee, Dan Weiner, and Sid Grossman.6 Unlike his peers, Webb was comparatively new to photography; he called his arrival in New York "the beginning of my career in photography." Several people, including Paul Strand and Roy Stryker (for whom he eventually worked), advised him to go back home to a "safe" job inDetroit. "How lucky I was to refuse [their] advice."

How lucky we are as well. Alfred Stieglitz, Webb's mentor and friend, was right: there is in Webb's New York photographs a tenderness without sentimentality that set him apart from his peers. As Stieglitz knew, photographers tended to portray New York as hardboiled or ironic or lyrical or messy, but never with tenderness. The word was not then associated with the city. (It rarely is today.)

There is also in Webb's New York a sense of regenerative exuberance that stemmed partly from the war. Following the allied victory in Europe and the liberation of millions of prisoners from Hitler's fallen Reich, people throughout the West began to hope for a unified world ("One World") devoted to peace, freedom, and harmony among nations. But the exuberance did not last. Visions of "One World" vanished after Hiroshima, the rise of Soviet aggression, and the specter of a third world war. As a result, 1945 ended on "a mixed note of gratitude and anxiety," as Ian Buruma notes. People had "fewer illusions about a glorious future and growing fears about an increasingly divided world." They wanted above all to get on with their own lives. "During a worldwide war, everywhere matters. In times of peace, people look to home." Todd Webb's New York is a symbol of America's home in the wake of war, in which people have retained their faith "One World."

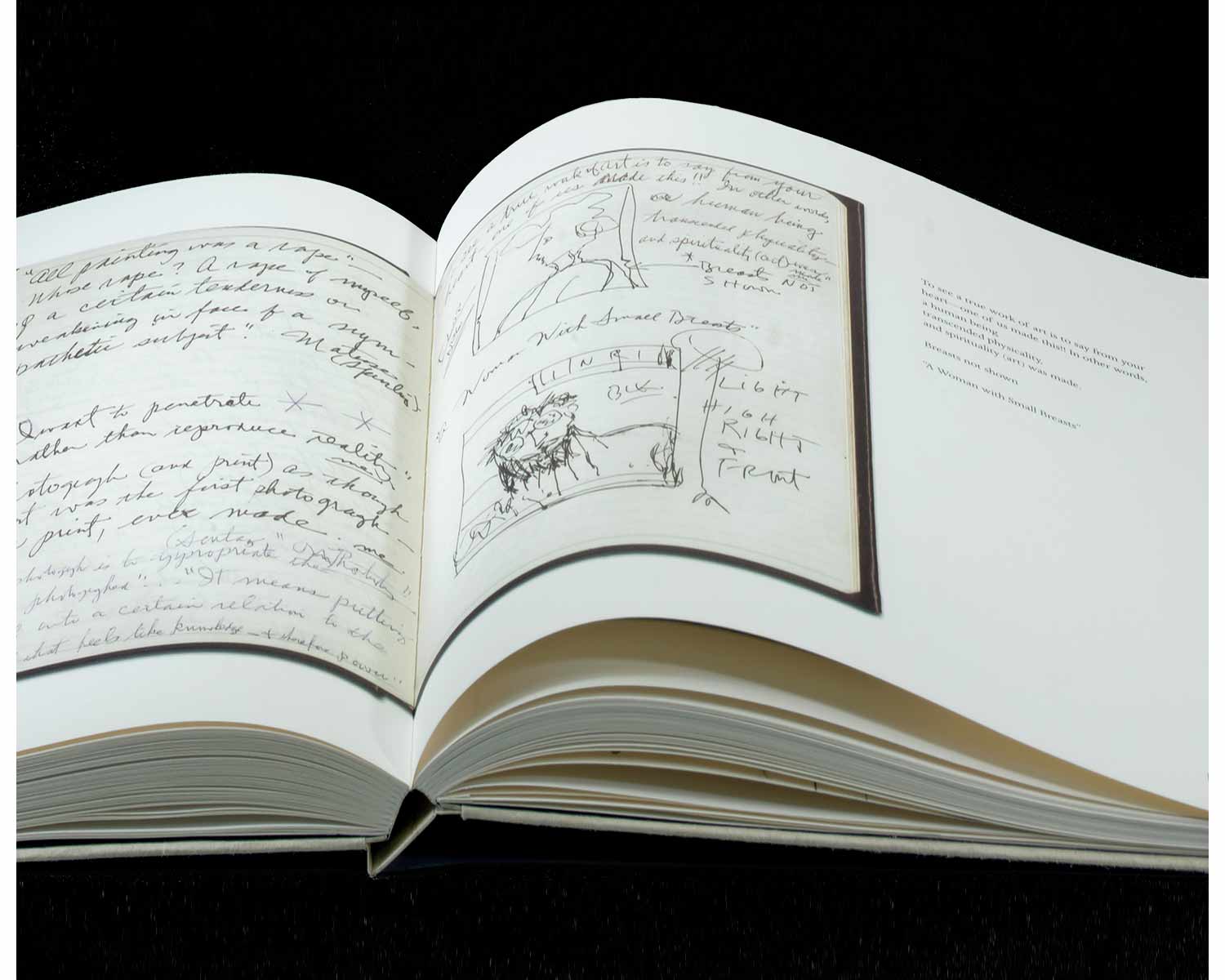

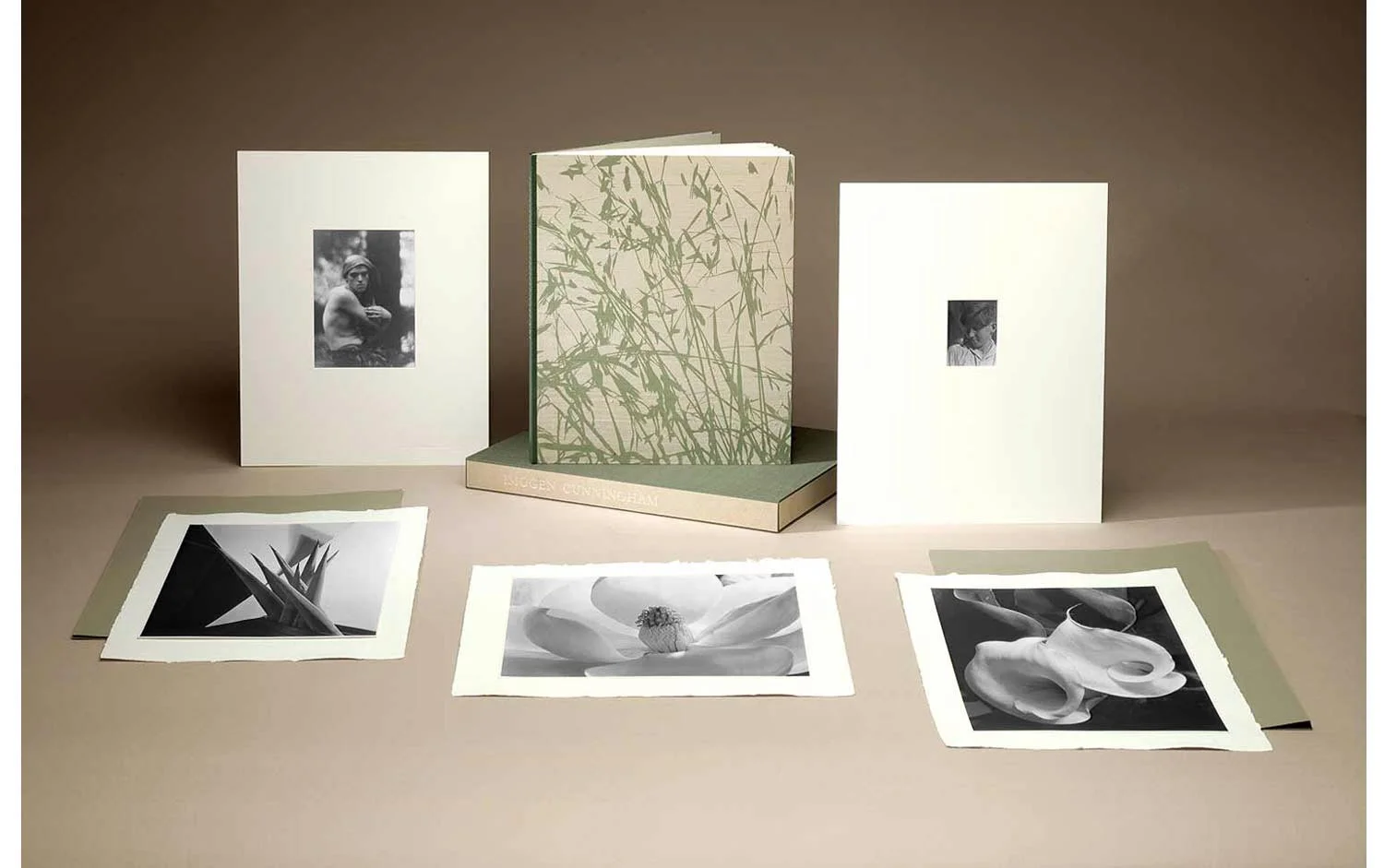

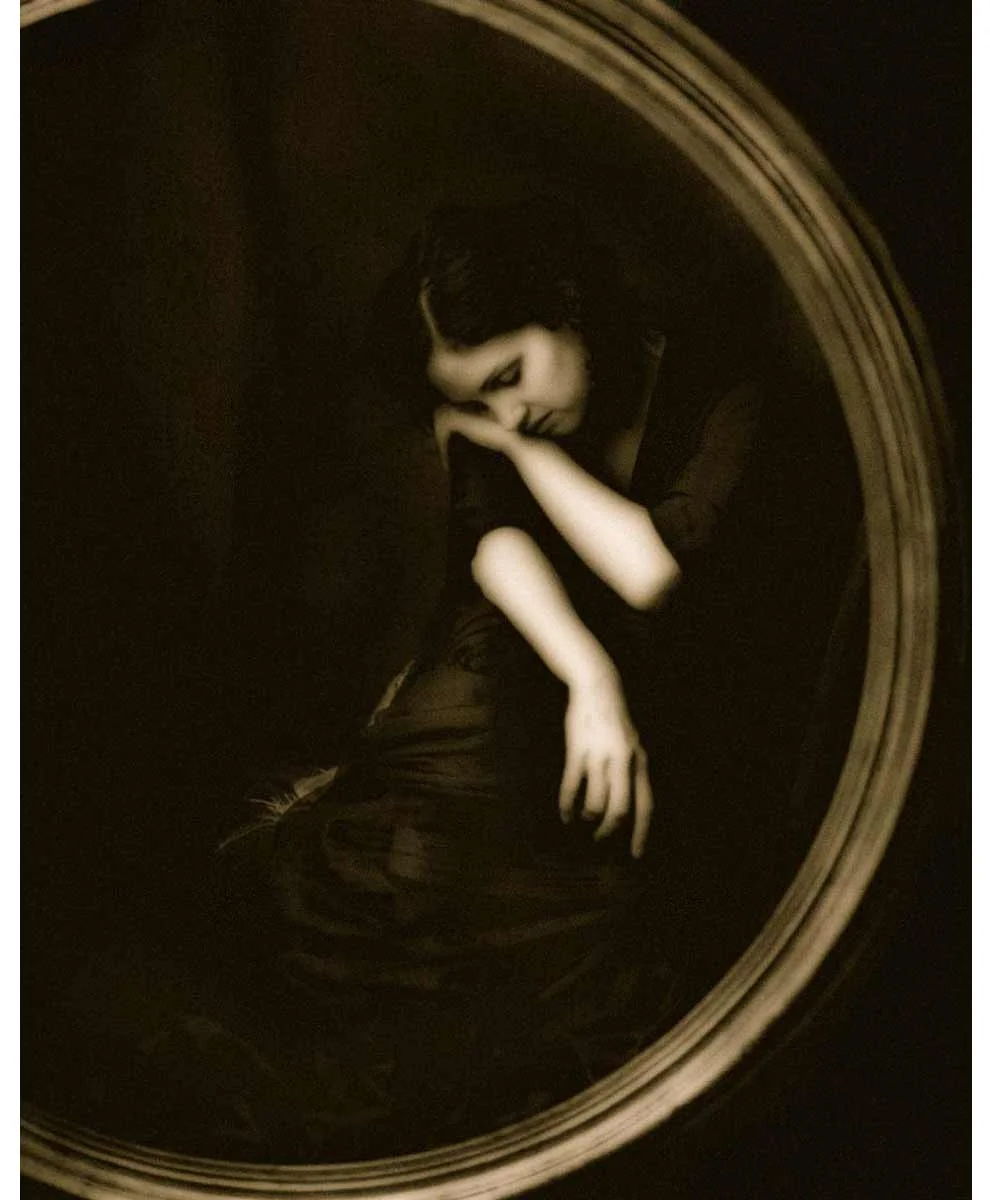

JOHN STAUFFER ON WOMEN IN PHOTOGRAPHY

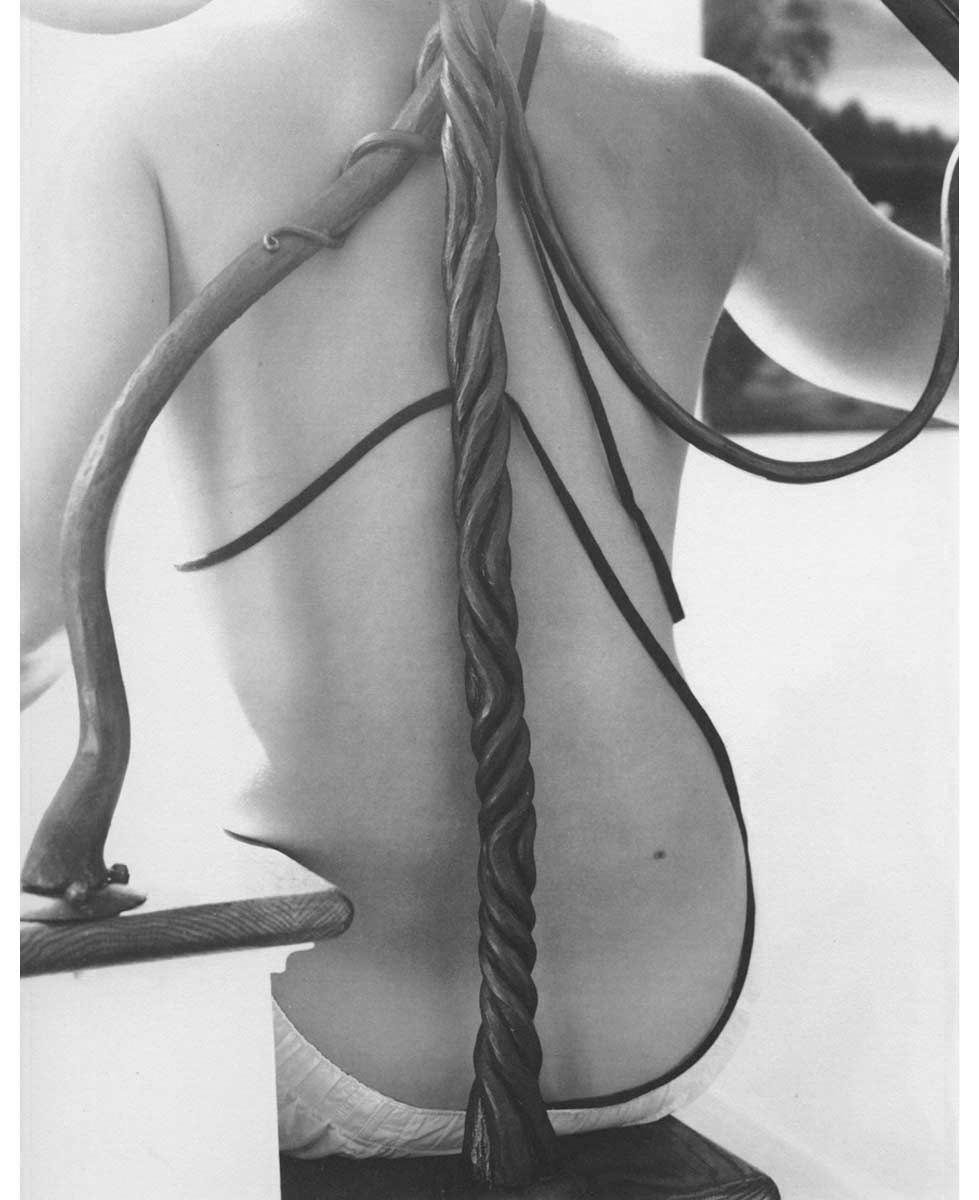

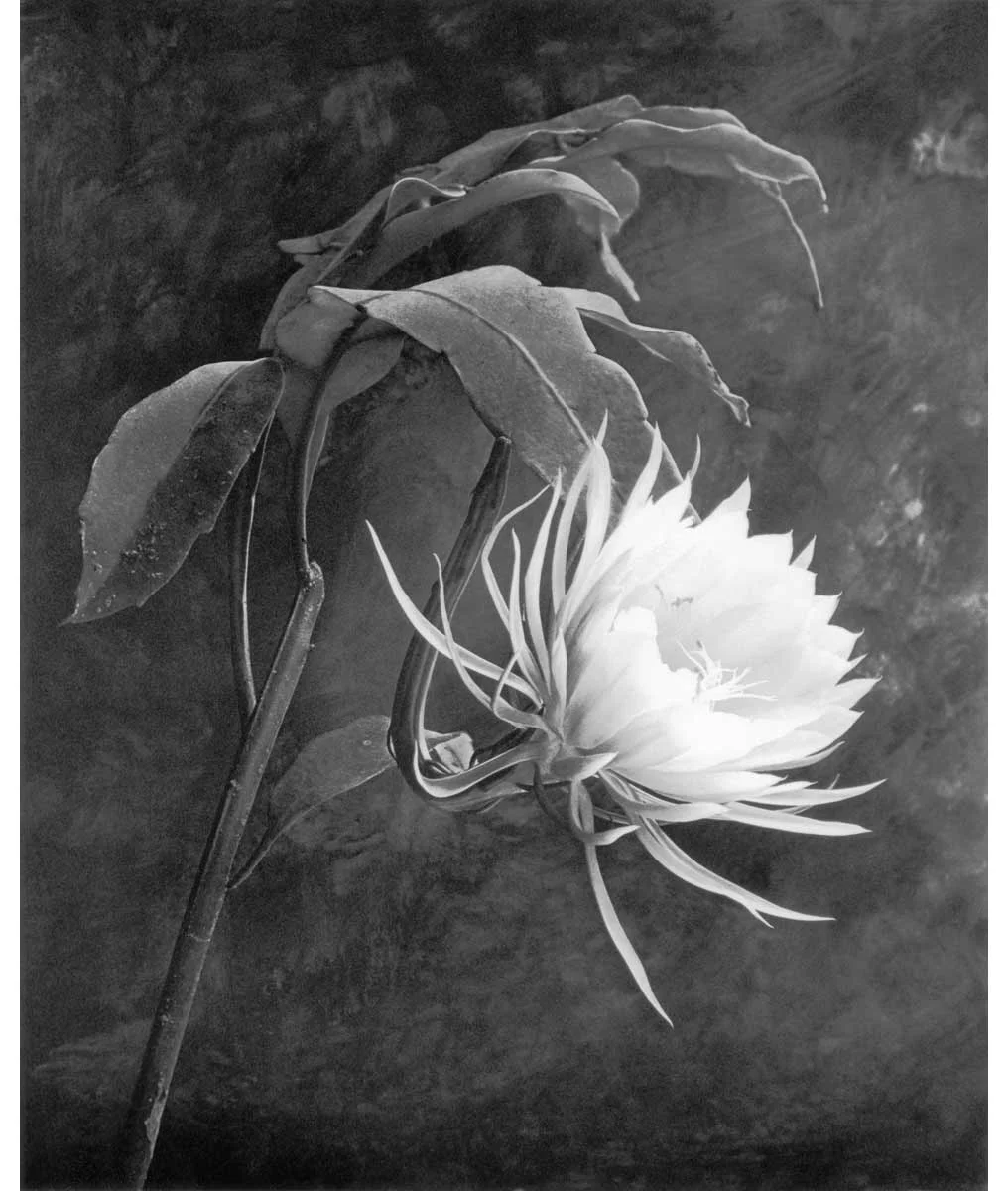

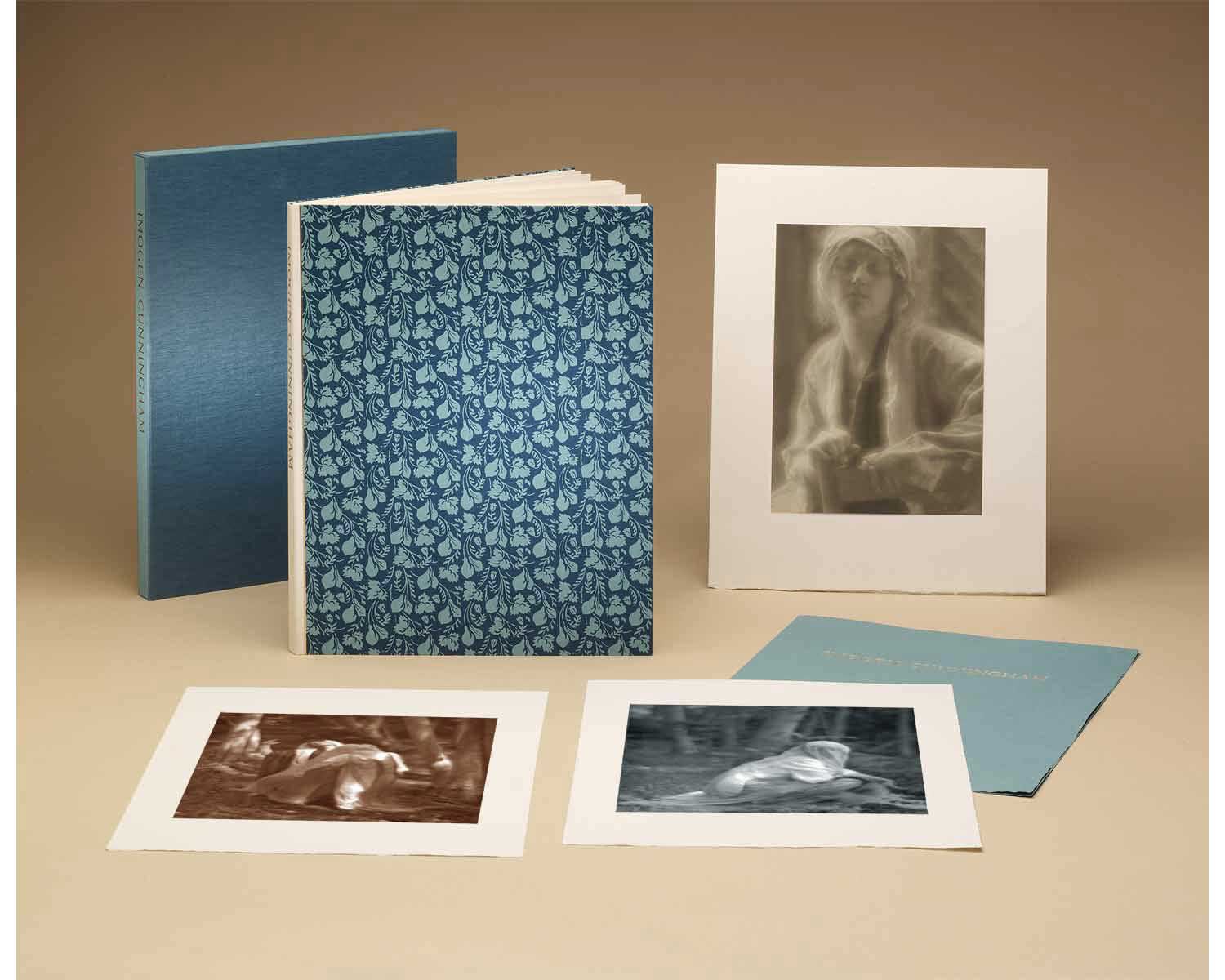

Imogen Cunningham: Family

Cunningham knew that women faced formidable social and economic barriers...but she also recognized that as a profession, photography was comparatively open to women. Not only was there the force of Käsebier, but Jessie Tarbox Beals and Frances Benjamin Johnston were prominent photojournalists, and the San Francisco Pictorialist Annie Brigman had recently been published in Camera Work. Indeed women had played important roles in photography from its inception. Constance Fox Talbot, Henry's wife, was one of the very first photographers; Nancy Hawes hand-tinted Southworth and Hawes' daguerreotypes; and Julia Margaret Cameron was among the nineteenth-century's most accomplished portraitists. Before the Civil War there were thirty-nine professional women photographers on the west-coast alone. "Photography is the democratic art," Cunningham said in her manifesto, because it depicted "the life of the masses" and accepted women.

Photography's comparative openness toward women was due to several factors. There were few barriers to entry; start-up expenses were modest; and the profession required no formal apprenticeship in which masters could exclude women. Then too, photography did not suffer from the myths of genre superiority that plagued painting and sculpture, whose cultural gatekeepers excluded women from exhibitions and museums.

The main argument of Cunningham's manifesto, however, was that "women as well as men need to be granted the right of self-expression through work." Women, like men, wanted fulfilling, creative professions without having to sacrifice marriage and "the care and rearing of children." Cunningham no doubt imagined herself eventually marrying and having children while remaining devoted to her profession. Photography was in this sense an ideal profession, and it could have "an enlarging effect upon the home." Why? Because "being devoted to one's work is much like hearing a great Wagnerian opera with one's soul open. The energy and vitality of life seems for a time sapped but comes back in renewed quantity and quality."

...It was as if Cunningham's manifesto/artist statement prepared her for what was soon to come. Two years after publishing it, she married Roi Partridge, an accomplished etcher. Ten months later, in December 1915, she gave birth to their first child, Gryffyd, followed by twins, Rondal and Padraic, in 1917. Partridge did not share her New Woman values; he taught art at Mills College while also creating his own art, and rarely contributed to childcare. And so for the next decade and more, Cunningham heroically juggled career and motherhood by focusing on subjects at home: her children and the plants in her garden. In this she became a model for subsequent generations of female photographers (one thinks especially of Sally Mann's Immediate Family).

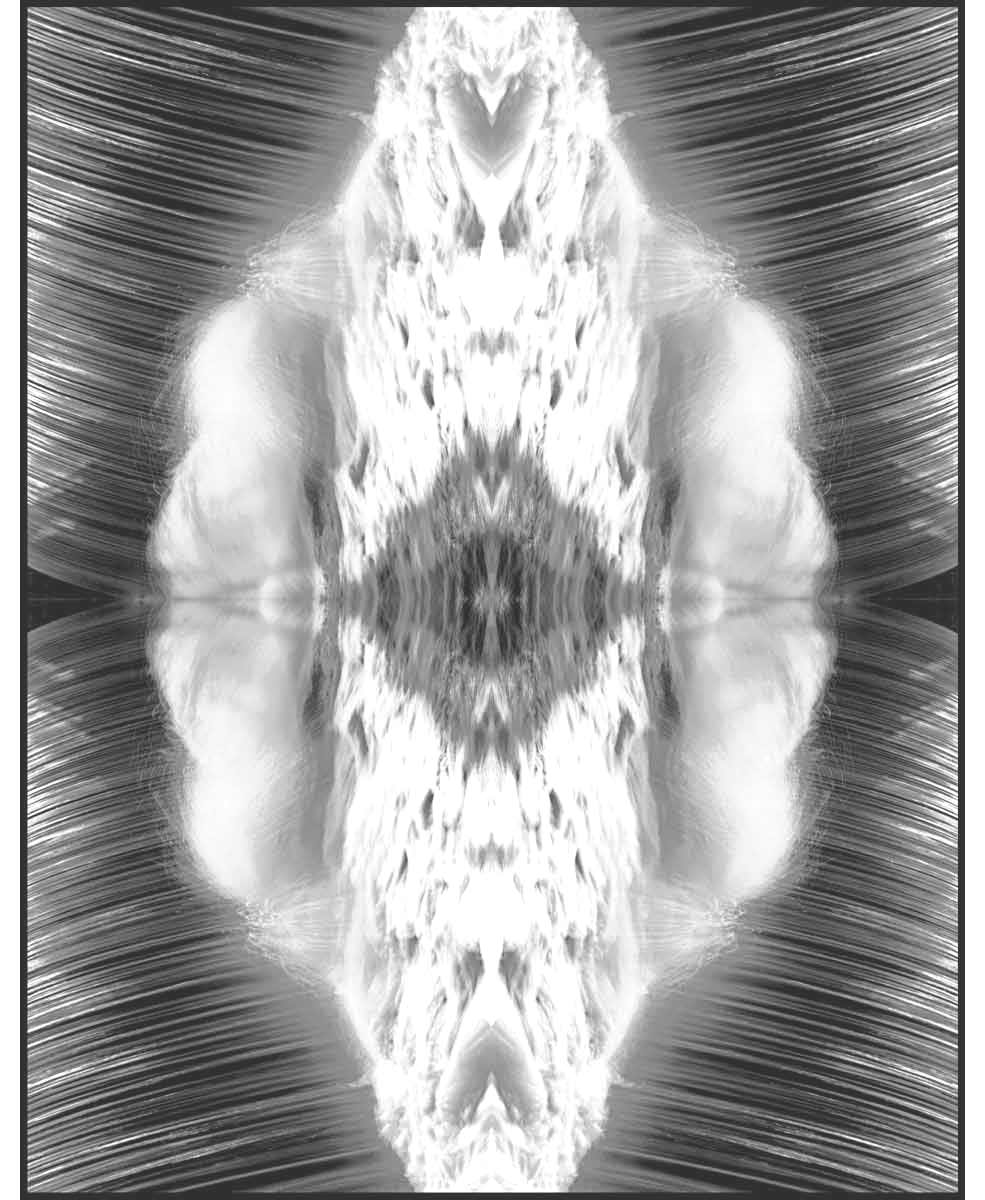

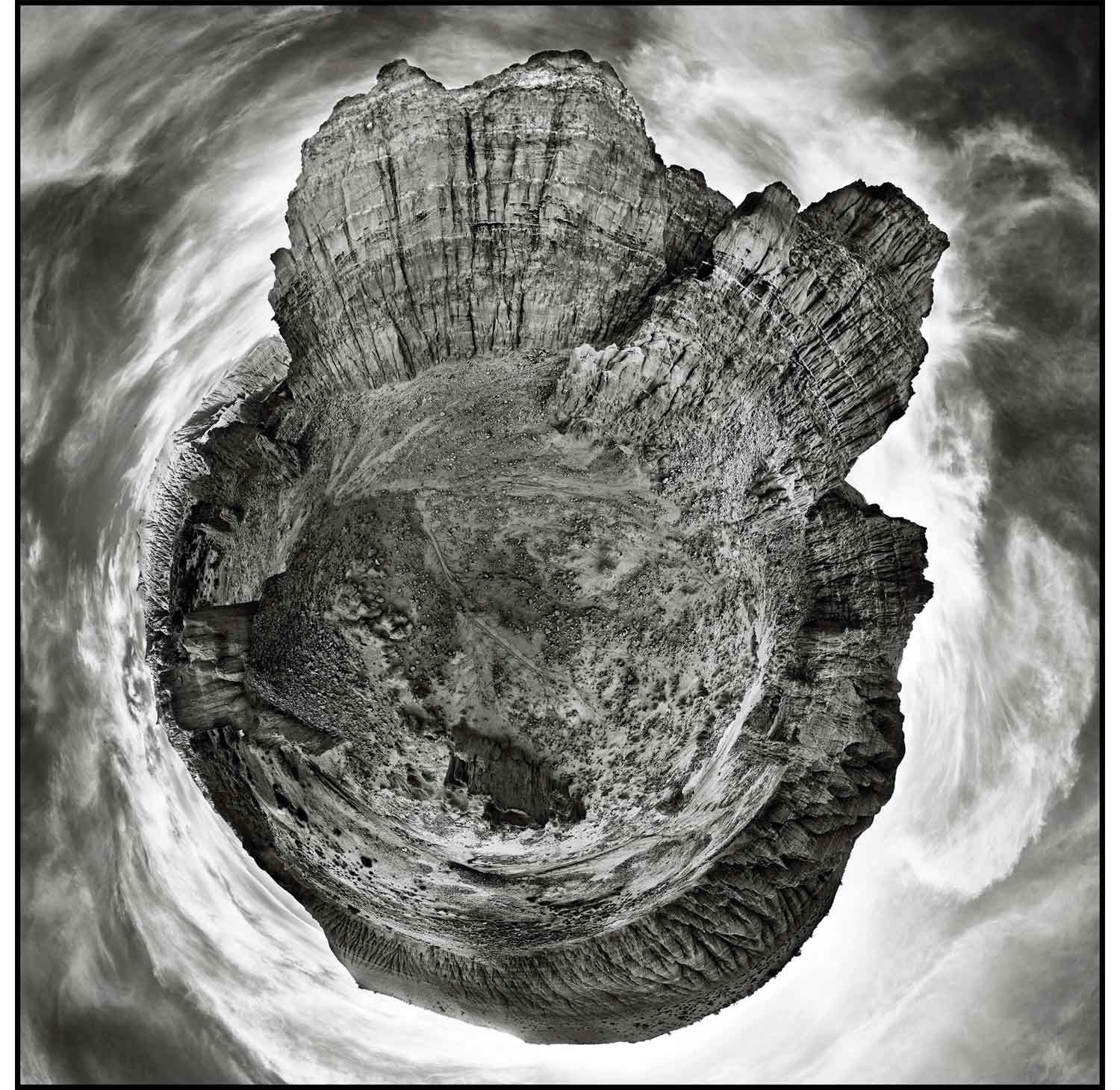

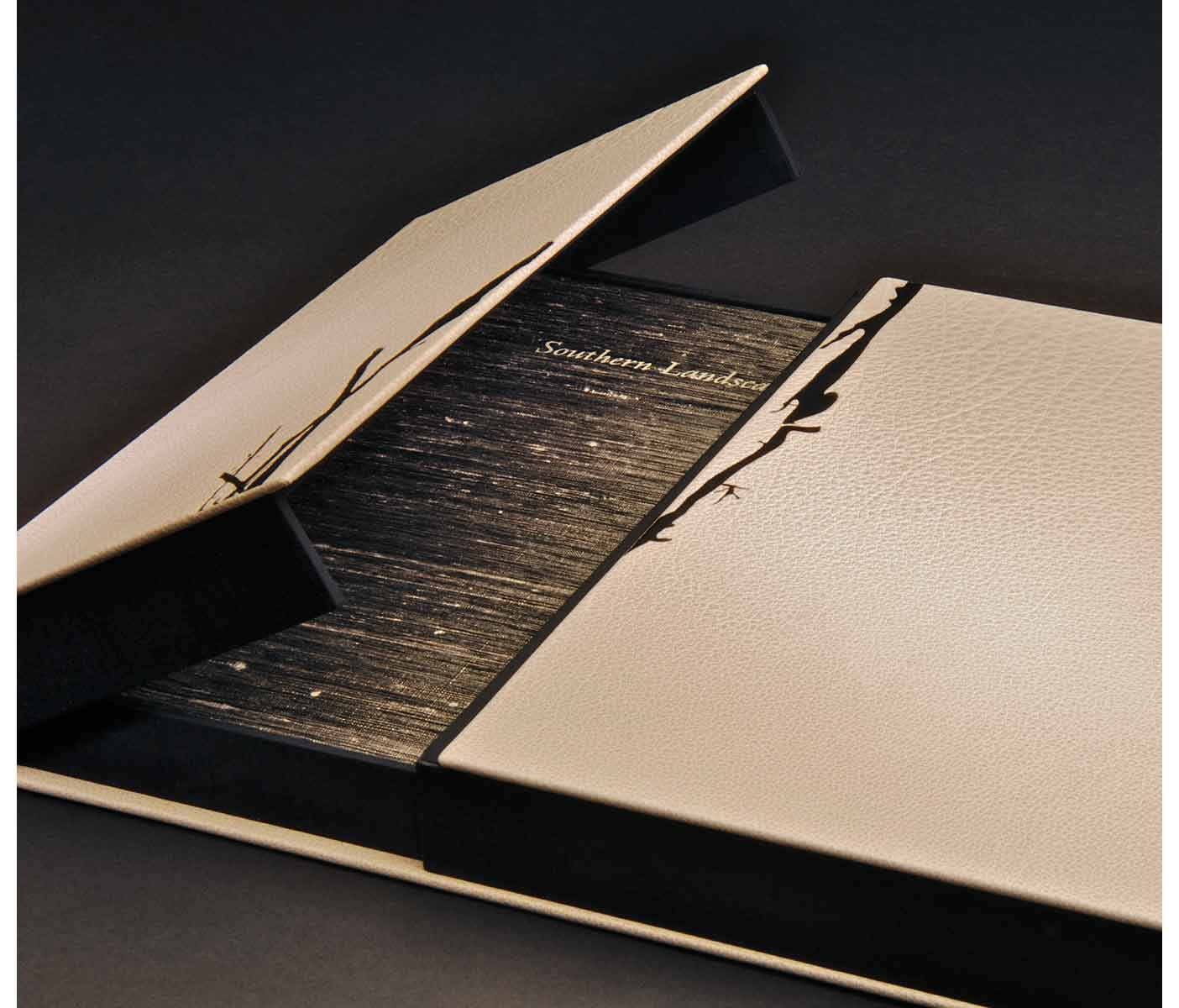

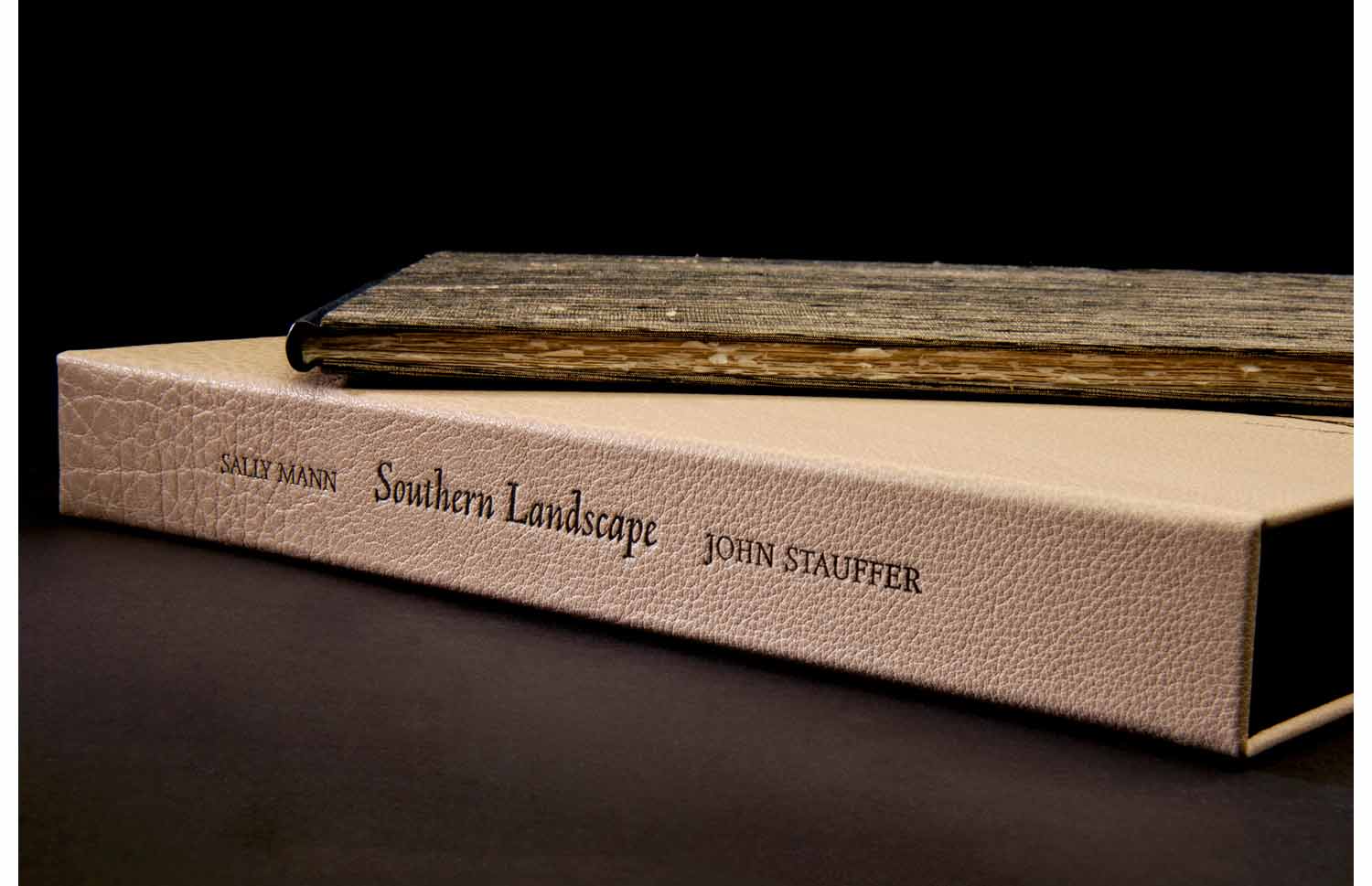

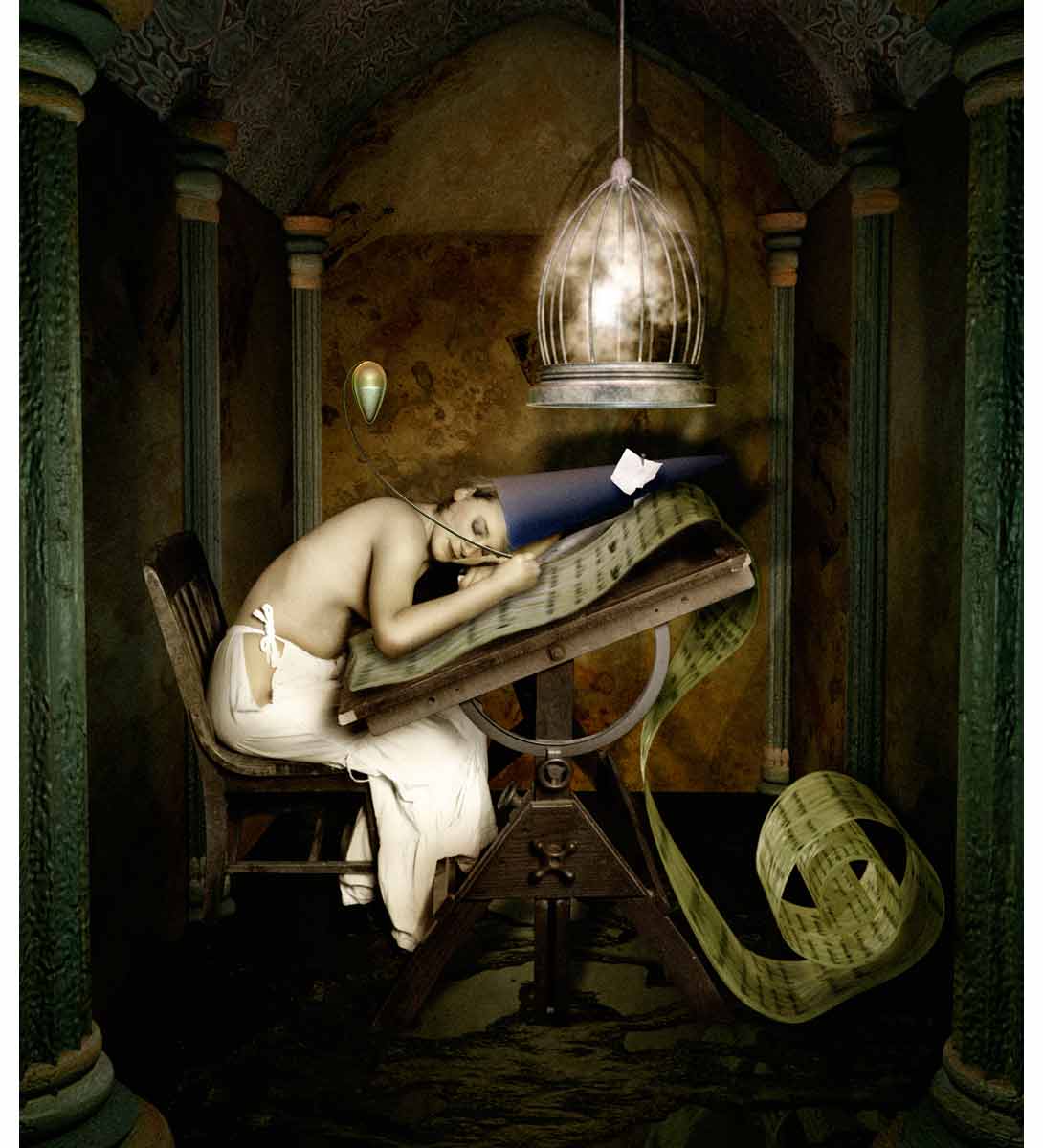

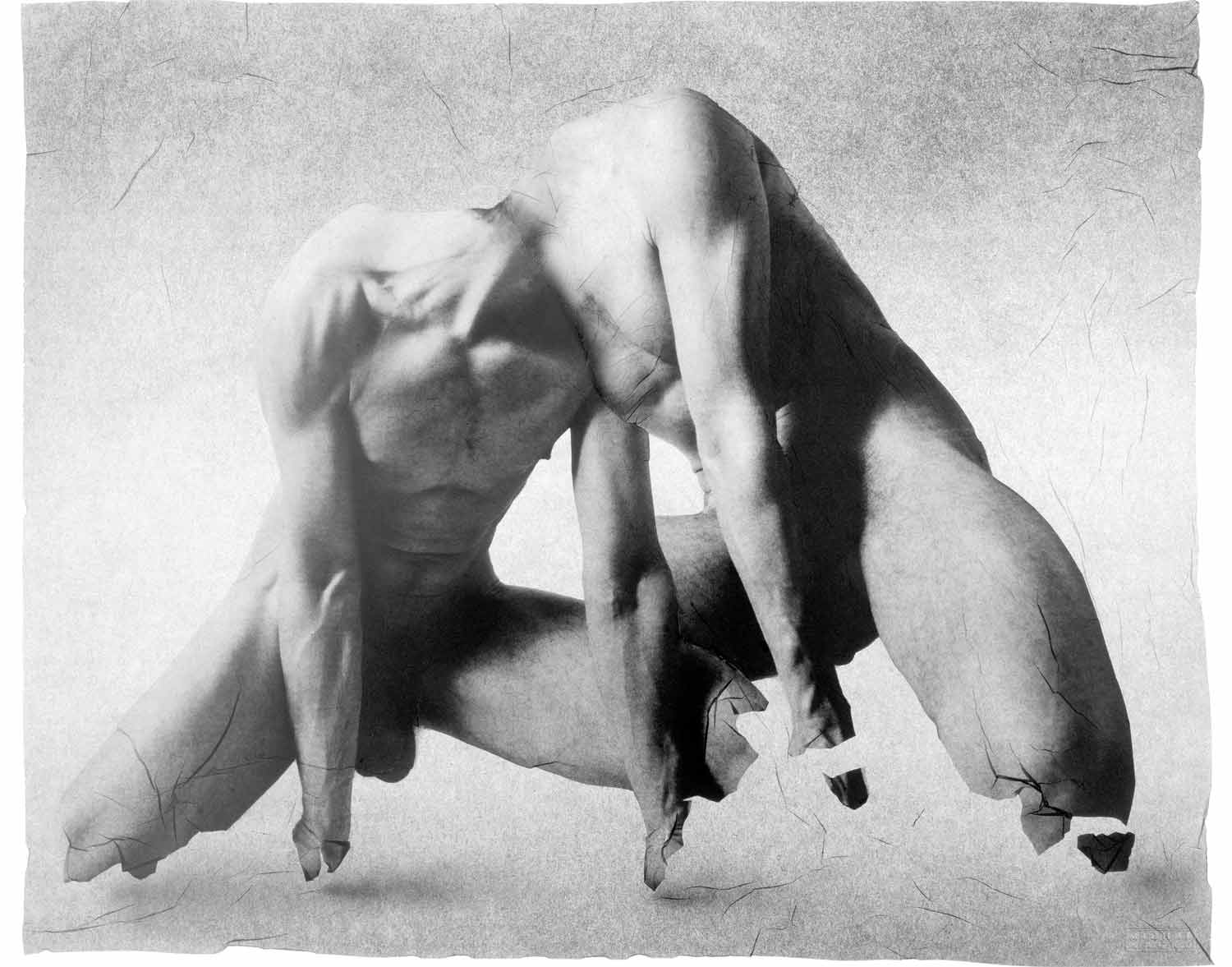

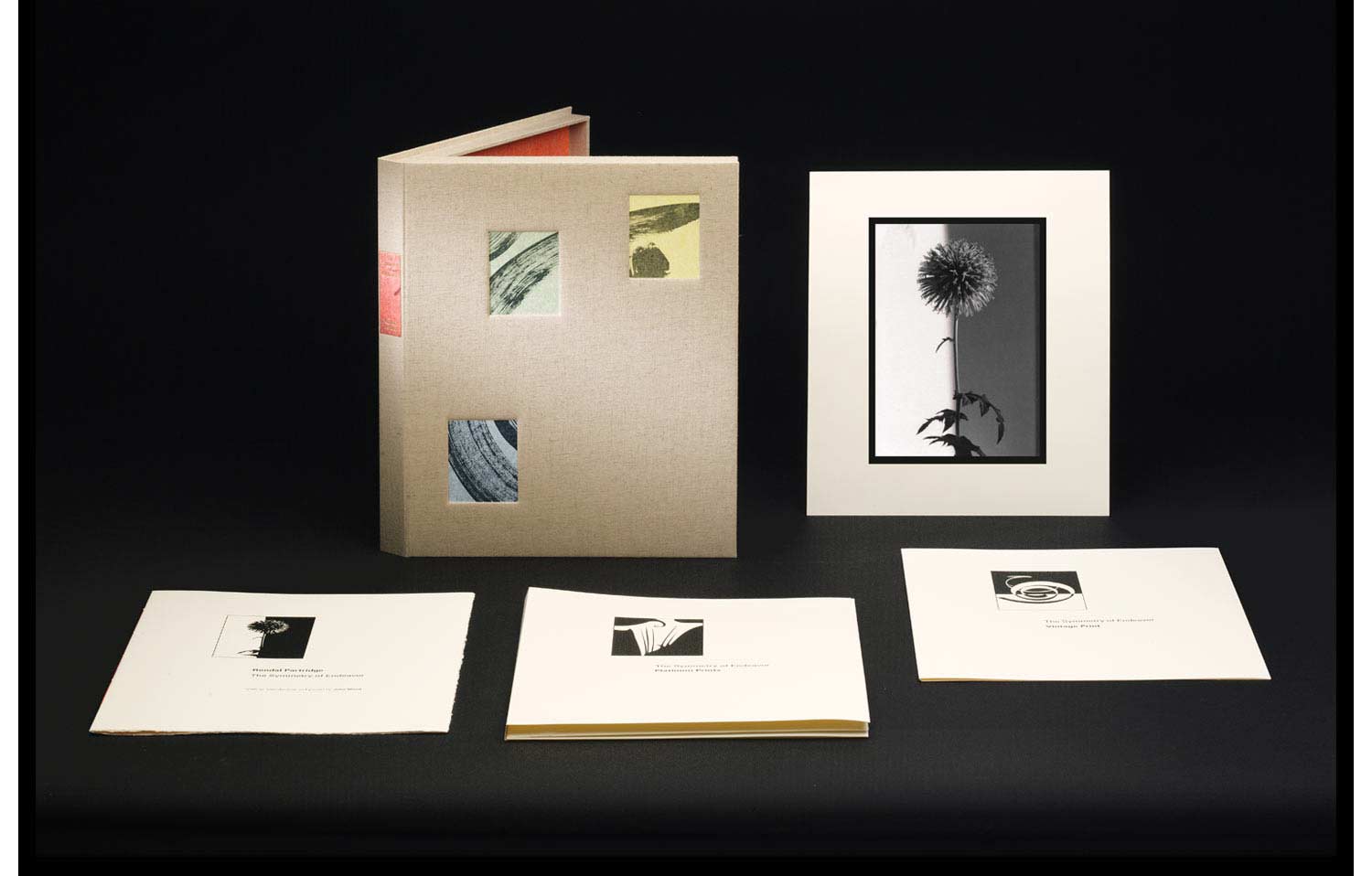

JOHN STAUFFER ON SALLY MANN'S

Southern Landscape

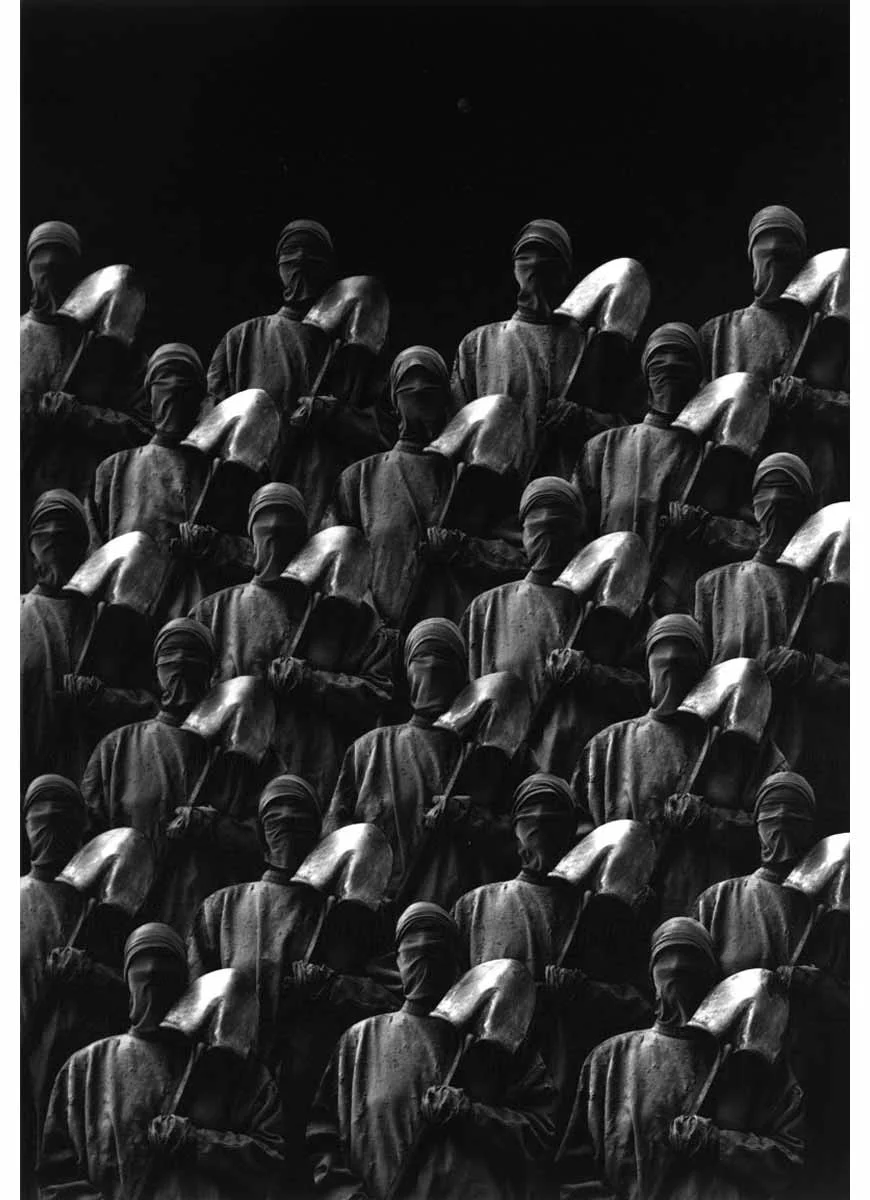

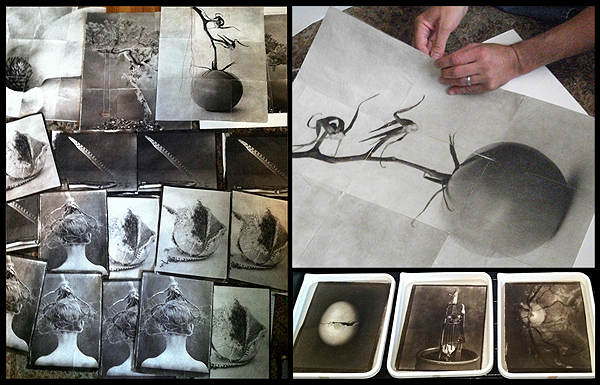

Mann's photographs, especially her landscapes, are also intimately connected to her Southern identity. In her Massey lectures she emphasized that we cannot understand her art without acknowledging her Southerness. "Maybe nothing so engages the Southern heart as a good piece of family land," she said, referring to herself. Born and bred in Lexington, Virginia, she lives with her husband Larry on a farm partly inherited from her father, and she has said that she will be buried there as well. Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are also buried in Lexington. Mann was born in Jackson's home, and one of her early photographic projects was to restore, print, and file glass negatives of Michael Miley, who is known as "General Lee's photographer." Lee and Jackson are of course the twin gods of Southern memory, a kind of Father-Son duo. Their "last meeting" before Jackson was killed at Chancellorsville, with Lee astride "Traveller" and Jackson on "Little Sorrel," is an iconic image, among the most popular Southern historical prints. You might say, then, that Lexington, Sally Mann's home, is the Jerusalem of the South.

Perhaps it is no wonder that Sally Mann is drawn, both in her images and the literature she reads, to the gothic, with its eccentrics, its haunting, and its unruly landscapes. "I think the South depends on its eccentrics," she has said, and she considers herself one of them. Her work undermines prevailing platitudes, from perceptions of children to the South's "Lost Cause," which ignores the horrors of slavery and Jim-Crow segregation and presents the Old South as a utopian paradise. She named her son Emmett, in part after the young Emmett Till, whose lynching in 1955 sent shock waves throughout the country, exposing the savagery of Southern segregation; and she photographed the spot where Till's body had been dumped into the Tallahatchie River. She aptly revised Flannery O'Connor's understanding of the South as "Christ-haunted": "I say it's death-haunted." It is haunted by (among other things) the deaths of slaves, the deaths of its white men during the Civil War, and the deaths of lynching victims during Jim-Crow segregation. And she is explicit in connecting her photographs of the Southern landscape to the South's haunted past: "The pictures I took on those awestruck, heartbreaking trips down south were pegged to the familiar corner posts of my conscious being: memory, loss, time, and love"...